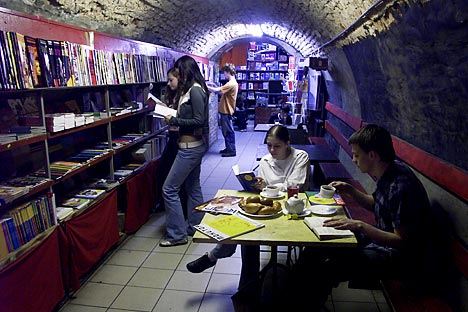

While indie booksellers are struggling in Moscow, they are spreading in the regions: in Penza, Smolensk, Novosibirsk, Voronezh, Vladivostok and other mid-sized cities. Source: RIA Novosti / Dmitry Korobeynikov

Just off Moscow’s Tverskaya Ulitsa—home to the Ritz Carlton, Tiffany’s and some of the most expensive real estate in the world—there is a small yellow arch inscribed with the word “knigi” (books). Inside, Falanster has little decoration to speak of, save for a poster of Che Guevara by the cash register. Customers bump into each other as they wander through the small room. And everywhere—stacked in piles, spilling out of shelves—are books.

In May, Russia’s most powerful publisher, Eksmo, announced that it was acquiring its main competitor, AST. Eksmo and AST publications, which range from cookbooks to fantasy novels, account for around 40 percent of the Russian book market; in some areas, like fiction, their dominance is near-total.

But as the Russian book market consolidates, independent publishers have a system of life support: small stores and cafes like Falanster. Although their ranks have diminished, a few have survived to maintain a market for independent books—and inspire new allies in Russia’s regions.

“It’s very difficult to fight against [monopolization],” said Boris Kupriyanov, one of Falanster’s founders, as he smoked a cigarette at a cafe across the street. “It’s only possible to create horizontal connections between publishers and stores.”

The relationship between small publishers and shops began in Moscow in the early ‘90s, when a group of friends gathered in an apartment on Tryokhprudny Pereulok to discuss books and music. This informal group would turn into publishing house OGI, as well as a parallel set of underground cafes that stage concerts and readings, and sell independent books.

“We looked at American examples where there are combinations of bookstores and cafes,” said founder Dmitry Itskovich in an interview at OGI club Zavtra. “In Moscow, it’s more unique, and got more attention. We had the first 24-hour stores.”

OGI heralded a wave of post-Soviet independent publishers. Perhaps the most successful, Ad Marginem, released early works by writers like Vladimir Sorokin and Lyudmila Ulitskaya (both of whom now work with Eksmo). Ad Marginem and other publishers also opened their own shops, alongside small non-publisher stores like Letny Sad and Grafoman.

“They were all located in very strange, very cheap places that had either a purely symbolic rent, or no rent at all,” Kupriyanov said. Often, this meant courtyards and alleys.

However, in the mid-2000’s financial help from sponsors dried up, and many shops were forced to close. Meanwhile, big publishers began exerting pressure on those that remained.

“Books from small publishers started to end up in the bowels of stores,” said Alexander Ivanov, head of Ad Marginem. “And naturally, our sales started to decline.”

Founded in 2002, Falanster rented its own commercial space, and was one of the few independent shops to survive these years. It’s organized as a cooperative, an unusual model in today’s Moscow. Members divide responsibilities evenly, from accounting to sweeping, and prices are kept lower than at many bigger stores.

“We wanted to have a different relationship to books, a more humanist approach,” Kupriyanov said.

Independent books compromise a tiny percentage of today’s market. Small St. Petersburg press Ivan Limbakh, for example, publishes 15 to 20 books per year, at around 2000 copies each; in contrast, AST releases around 800 titles a month, and has the resources to distribute them all around the country.

“Stores aren’t in the habit of distributing with small publishers,” said Irina Kravtsova, head of Ivan Limbakh. “They don’t help us at all.”

At Falanster, however, around 85 percent of the books come from small publishers. On rare occasions, it also publishes titles itself (most recently, “Dostoevsky: Economist,” a set of essays by Italian Marxist Guido Carpi). Many of the authors on the shelves are leftist, but visitors are as likely to find Ayn Rand as Howard Zinn.

“We choose books according to one principle: whether it leads to some kind of thought,” Kupriyanov said.

There are currently 10 or so small independent bookstores in the capital. Falanster has opened a second location in modern art center Winzavod, as well as a sister store, Tsiolkovsky, in the Polytechnical Museum; other independent store-cafes include Dodo and Nina. Most of them double as social centers, organizing festivals and other events.

But their existence can be tenuous. In June, OGI’s original cafe on Potapovsky Pereulok shut its doors, causing collective grief among Moscow’s intelligentsia.

“A large part of my life is connected with OGI,” said Kupriyanov, who signed Falanster’s founding documents in OGI’s basement. “It was practically the only club where poor and unglamorous people could go.”

Itskovich, who was no longer the cafe’s owner, said he didn’t know the exact reason for the closure. “They probably raised the rent.”

But he said it wasn’t an ill omen. “They were just tired of it. Every club has a shelf life.”

While indie booksellers are struggling in Moscow, they are spreading in the regions. In the past two to three years, readers in Penza, Smolensk, Novosibirsk, Voronezh, Vladivostok and other mid-sized cities have gained their own independent shops.

“Before we opened, there weren’t any places like this in Perm,” said Mikhail Maltsev, head of Piotrovsky, which opened in the Urals city two years ago. “Among our friends, we all saw and heard that people had a need for intellectual literature.”

But like its peers in the capital, Piotrovsky has difficulty paying rent. “It’s still too early to call it a success,” Maltsev said.

This winter, Falanster and Ad Marginem created an alliance to help strengthen ties between independent publishers and stores across Russia. “Small publishers make decisions very quickly, and in many centers. The task is to create structures between them,” Ivanov said.

In the end, small publishers and stores may need to unite to survive. “It’s not a competition,” Kupriyanov said. “We all depend on each other.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox