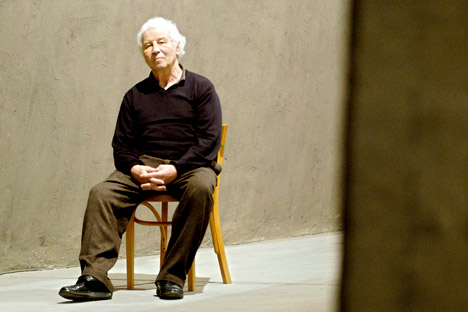

Ilya Kabakov: The Soviets made a mistake by allowing a huge amount of Western cultural works into the country. Source: AFP / East News

Ilya Kabakov grew up in the Soviet system, but his art knew no boundaries. Considered one of the world’s greatest living artists, Kabakov today lives in the United States. He spoke with Afisha magazine about creating art in the Soviet era and contemporary art today.

Afisha: How did you become familiar with unofficial art?

Ilya Kabakov: In Stalin’s time, everything that an artist created was controlled. Commissions crawled into studios and heaved aside canvases. In the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras, no one was interested in what you said in your kitchen or did in your studio. Those were wonderful times.

Ilya Kabakov was born in the Soviet Union, in the city of Dnepropetrovsk, which is now part of Ukraine. He went to art school in Moscow and became known as one of the founders of the Moscow Conceptual School. He began his career as a book illustrator, and was an active participant in dissident exhibitions. Kabakov’s works Beetle ( $5.8 million, 2008) and Luxury Suite ($4.1 million, 2006) are two of the most expensive contemporary Russian works ever sold. His work can be seen in the Tretyakov Gallery, the Hermitage, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and other prestigious world collections. He lives and works in Long Island.

In Moscow around 1957 an amazing underworld of unofficial art blossomed. There were artists, poets, writers, homegrown theologians and composers. These people had no exhibitions, no critics, no galleries, and no sales. In a bomb shelter, you know, everyone is a friend, everyone shares, a sandwich, an apple – everyone’s in the same boat and therefore everyone understands and supports each other. When the doors of the bomb shelter opened in 1987, each person found his own destiny.

Afisha: When you went abroad, did you feel relieved?

I.K.: When I left, I met the people I’d been dreaming about. This reminds me of Anderson’s story of the ugly duckling. Swans actually existed.

I discovered the most wonderful period in the Western art world – from the late ‘80s to 2000. This was the heyday of the museum and exhibition business in Europe and America. I found my own kind. I was immensely happy, like a musician who moves from one concert hall to another and gives concerts everywhere.

Besides that, everyone wanted to see what came out of “North Korea” and that’s what made my exhibitions possible. I was Sinbad the Sailor, who was supposed to tell the West about the terrible pit from which I was able to bring signals and stories. I thought that I’d had enough anger, despair and anguish for my entire lifetime, but as it turned out I was cleansed by leaving my country and now I have nothing more to say.

Afisha: But wasn’t it offensive, that the attitude toward you as a person from the Soviet Union superseded the attitude toward you as an artist?

I.K.: No, the art world was completely apolitical. The century I was born in was completely oriented toward art. And I myself perceived Soviet power not as political, but a power of climate. Soviet power was perceived as an eternal climate of darkness and rain. I had no desire to protest – you can’t stick your head out the window and shout “Stop raining!”

Afisha: How did the idea of total installations first occur to you?

I.K.: This occurred to me in Moscow, in 1984-1985, when I had already designed different installations that were impossible to do in Moscow. Only when I left did it become possible. The Soviets made a mistake by allowing a huge amount of Western cultural works into the country. We had to be fenced off, like the Nazis, but in the Soviet Union, Western art was shown in the museums, and Western music was performed in the conservatories. The libraries were full of the best translations of Western literature. Despite the Iron Curtain, Western art was always present.

Teachers told us, “you’re already 18 years old and you haven’t done anything, but Raphael had already painted the Solly Madonna by your age.” My birthplace was instinctively connected with the West, and saying “there” and “here” you would always be sitting on two chairs. Today I think that many understand this.

Surrounding reality was a dreary, swinish savagery. The contrast between that and the oases, the Pushkin Museum, the Tretyakov Gallery, the Conservatory, and a number of libraries, that was the Soviet life that created fertile soil for art.

Reading books, you looked at your surroundings from the perspective of what you read. You could look at your environment with a different attitude – perhaps as an ethnographer, a member of a British geographical society who observes cannibals on a trip to Africa. Or you can assume an angry attitude, “Why do I have such a dog’s life?” This despair! And yet a third – you’re Gogol’s little man with the overcoat. Despite the ideological pressure, you have your own ideals, your own overcoat, and your screaming consciousness.

On the one hand, you’re an observer, but on the other you’re a patient. What the current generation never experienced is the insane fear that the authorities can pull you off the street and throw you in jail. This fear is difficult to describe today.

This is the abridged version of this interview first pubslished in Russian in Afisha.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox