Russia is famed for its classical musical, ballet and drama, which have a long and rich history and an ongoing influence on world culture. Source: RIA Novosti

Chekhov's plays were a breakthrough in world drama in the first quarter of the 20th century. Their plots distinguished them from traditional dramas of that time by virtue of their special psychological depth. Chekhov did not show the only true path to the salvation of heroes. Instead, he drew spectators into the study of everyday behavior of the characters and encouraged them to make their own conclusions.

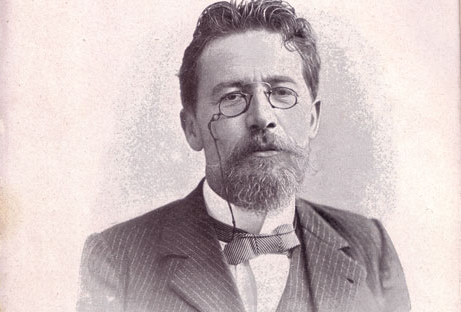

Anton Chekhov. Source: Open source

His work, alongside the works of Ibsen, Strindberg and Shaw, formed the basis of "New Drama," an important theatrical trend at the turn of the century. Outstanding playwrights revered Chekhov as the father of psychological theater. For example, Bernard Shaw called his play Heartbreak House a "fantasia in the Russian manner on English themes."

Tennessee Williams adored The Seagull and wanted to put it on stage in his interpretation for the rest of his life. This play, alongside Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard, has been translated into more than 80 languages and been staged countless times in the UK, Germany, France, Japan, the U.S. and other countries.

Stanislavsky's legendary "I do not believe it!" became a meme in the global theater community. A famous director and co-founder of the Moscow Art Theater, he was a stern coach for actors. His system of acting techniques teaches the actor to "live the role." Stanislavsky made his players investigate the identity of the hero step by step, find the similarities with their own feelings and then recreate them on the stage.

More than 100 years since their introduction, his methods are still taught in acting schools today and can count many movie stars as ardent fans – from Keira Knightley to Benedict Cumberbatch.

Mikhail Alexandrovich “Michael” Chekhov was a disciple and follower of Stanislavsky, but his system largely engaged in polemics with the precepts of the "teacher." Chekhov, in particular, suggested that a good performance required detachment; when performing a role, the actors must scrupulously copy the character, carefully observing their acting and checking themselves for naturalness, rather than identify themselves with the hero. Today, Chekhov's system compares with Stanislavsky's system in popularity. It is used, for example, by Clint Eastwood and Jack Nicholson. In the U.S. there is even an association of teachers working with the Chekhov acting technique.

Vsevolod Meyerhold created a special kind of theater that came to succeed folk performances on squares. The theater of the grotesque, as it would later be called, presumed utterly visual, bright and physically complex action.

It incorporated both dance and circus routines and cumbersome constructivist designs, which organized the stage space. One of the successful works of him as a director was his futuristic production Mystery-Bouffe, based on Mayakovsky's play of the same name.

Meyerhold also developed a system of work with the actors, the so-called "biomechanics", which became one of the strong points in Brecht's dramaturgy. The key element was the physical development of the role. Artists primarily mastered the gestures inherent to the character – it was through the precise movement that psychological similarity of the actor and the character was achieved.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox