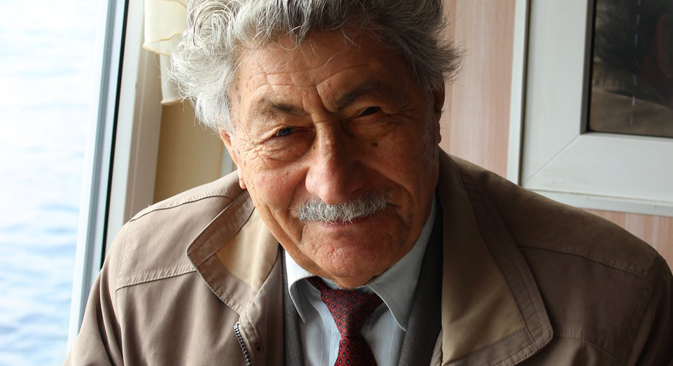

Pavel Rubinchik. Source: Personal archive

Pavel Markovich Rubinchik’s first experience of war happened when he was just 13. Two days before the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941, the boy was sent to a summer camp near Minsk, now the capital of Belarus. The approach of war was not yet tangible there; the children had fun and played football. But on the night from June 24 to 25, everything changed.

"It's time to go to bed, and we see the sun does not set. At 11, even at 12 at night – it doesn’t set. All night we were trying to figure out the cause. The bravest ones climbed the bell tower," says Rubinchik. The unearthly light turned out to be Minsk burning from incendiary bombs – the Germans were already approaching the city. "The flames stood 60 meters above the city, it seemed the night had vanished," says Rubinchik.

The camp organizers decided to move the children away from the Germans toward Moscow. The children had to run along a highway covered in black flames; attack aircraft had dropped incendiary bombs on the road. "We took all our belongings, but soon had to throw them away. I thought that my mother would punish me for it. Such a childish innocence," Rubinchik recalls.

But the boy was to become an adult in an instant when he saw death for the first time: “We came under fire. There are shouts of 'Get down!' We get down, both children and adults. The time comes to get up and run on, but a boy next to me is down. I pull at him, but he does not get up. I feel him, and there is blood.

"We didn’t eat or drink, but only fell, got up and ran again. Only once did we lay down to sleep, but the night did not come again. The adults began to wake us up: 'The Germans, the Germans.' We took off our pioneer ties so that the Germans would not find them. And suddenly, here they are – in black uniforms and with skulls on their caps. The adults whisper: 'Carriers of death.' This was our first encounter with the Germans. They ordered the children and women to return to Minsk, and took the men away with them. They either shot them, or took them prisoner.”

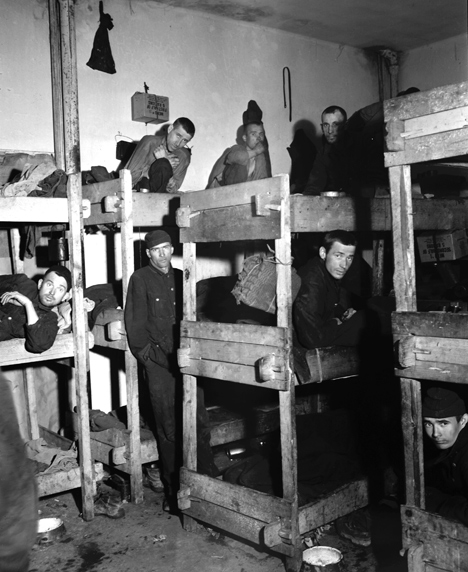

Soviet prisoners of war in the German POW camp Stalag VI. Source: The Hemer city archive

Rubinchik recalls how, having not eaten for three days, the band of children and their charges passed through a village on the road to Minsk. “We smelt the aroma of food,” he says, “and for the first time in my life I had to go up to a house and ask, 'Auntie, give me something to eat.' She gave me a cup of milk and a rye pancake. In the whole of the rest of my life I have not found a pastry as delicious as that pancake was. I kept asking friends, ‘Bake me the same!’ but they did not manage to make a tastier one."

Pavel's parents were nowhere to be found in Minsk, so he was soon forced to look for food again: "We climbed onto some abandoned freight cars and found some sunflower seeds there. Then we went to a burnt candy factory and found some flour. Being a Jew, I had to hide from the Germans. And so I could get into an orphanage it was decided to baptize me. They changed my name.

"On July 19, an order was issued for the Jewish people to assemble and move to live in a separate area. It was called the 'ghetto.' In the orphanage, we had been still fed, but the children there were already little skeletons. I was given a wheelbarrow. And for the next two months, I took these skeletons, emaciated with hunger, to the graveyard and dumped them into mass graves."

One day, Rubinchik was rounded up with groups of other Jews and packed onto a truck. “We were building a prison for the Germans – for deserters, cowards or dissidents. After that we were supposed to be taken back to the ghetto. We got into the truck. And suddenly we noticed that we had been traveling too long, on the forest road, but the city was not in sight,” he says.

“The adults recognized the area and said, ‘We are not going to the ghetto.’ And at that time the death camp near Minsk, where they burned and shot people, was already common knowledge. No one came back alive from there. They opened the gate, and we said goodbye to each other.

"Behind the barbed wire, they started to count us – every fifth was told to stand out. Three of the fifths were taken forward, had ropes tied around their necks and hanged. We were afraid to move. A German came forward and said, 'You have come to a facility where we forge weapons to defeat the Communists.'”

Rubinchik and other inmates were put to work in gun workshops assembling firearms, but the routine was gruelling and took its toll on the prisoners.

“We worked for 14-16 hours. We were fed only once a day with soup made of herring heads. That's why I didn't eat herring until two years ago. I could not even look at it. I survived only thanks to one German named Paul. He began to bring me pots to wash. And there were some food leftovers in these pots. That was my salvation."

However, as Rubinchik recounts, eventually things changed: "One day the Germans asked us where we lived in the ghetto, told us to get into the truck and drove us at night to see people we knew there.

“In the ghetto, acquaintances asked me if I wanted to go over to the partisans. This question sounded like a mockery. Of course I did. I was filled with such feelings of hatred and revenge! The Germans did not treat us as human beings. When we lived in the ghetto, each of us had a badge with a number of the house. If it turned out that one of the residents had disappeared without trace, and his death was not registered, they would shoot the whole house.

"To get to the partisans, I had to bring 50 rifle ejector springs from the plant. In the partisan combat group, weapons were few. They picked up abandoned weapons, but because of the moisture small parts, including springs, failed. For that reason, a spring was equal to a new weapon.

"At the plant in a concentration camp, I used to cover the weapon with oil,” explains Rubinchik. “I had to quietly pull out a spring and throw it into the soup in the pot. At the exit from the plant I was checked by a gendarme, while holding the coveted pot in my outstretched hand. If he suddenly took it in his hand, he would feel that it was too heavy. I would be shot at once."

Eventually, the time came to escape. As Rubinchik explains, they were surrounded by several rows of barbed wire; soldiers with dogs walked around the perimeter. But things did not go as smoothly as expected.

“A friend and I had planned to break out at night,” he says, “but suddenly we were gathered in the evening, and it turns out that someone else had attempted to escape. He was caught, beaten and hanged in front of us. But we still decided to flee. We thought that if this was to be our fate, we would hang there the next day too.

“We made a gap and fled to the railway. And suddenly, by pure chance, there was a freight train. We clung to it and left. My companion was dragged on the ground for a while, and then I pulled him up. After 20 kilometers, we jumped off the moving train and rolled down the grass. We were rolled and flipped. I began to feel myself – if my arms and legs were intact. I felt I was alive.

“After wandering in the forest for 10 days, we reached some partisan groups. My friend and I had such a feeling of revenge that we could not sleep at night, and kept bothering the commander: ‘Give me a task.’ We made him so tired of us that sometimes he gave us tasks from which previous groups had not returned. But, as you can see, I am alive."

Rubinchik recalls how he earned his first medal for military merit. "Later, when I already was a drafted soldier, I used to transport shells to the frontline. Suddenly we came under fire. ‘We are going to die,’ I think. I shout to the driver: ‘Let's go, now!’ but he is silent. I looked at him – he's all covered in blood, the cabin has been pierced. What to do? I sat behind the wheel and drove 40 kilometers at the very moment a counterattack took place."

During the war, I was wounded and shell-shocked when I was 17. “They came to bury me and by some miracle noticed that I was still alive,” he says. The young man was sent for treatment, and then began to look for his parents, finally locating them.

“After the war, my father forced me to study. I was a big guy sitting in school among children. I went through the war, but forgot how to read and write. Only the teacher of German was happy with me. After all, in a concentration camp you could not fail to obey the command of a German if he addressed you. That's why we crammed German and memorized everything. Otherwise – death.”

Today, Pavel Rubinchik is the head of the St. Petersburg Society of Jews – Former Prisoners of Fascist Concentration Camps and Ghettos, and the creator of the city’s Holocaust Museum. Since he had been a prisoner of fascism for two years himself, he decided to bring together all those who had survived famine, overwork and the eternal fear of death.

Initially, the organization included 550 people from St. Petersburg and 70 from Russia’s North-West Federal Region. However during the course of its 20 years of existence, the society has shrank precisely by half. "Many do not leave their home anymore. So we try to support them, send visiting nurses to them. We even have a German volunteer," says Rubinchik.

He sighs. "And we visit cemeteries so often that we jokingly call ourselves a funeral team. My turn will come soon, too. I tell people, 'it is time for me to leave.' But they still do not want to part with me."

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox