A still from The Last Emperor. Bernardo Bertolucci's film familiarised Western audiences with Pu Yi's life. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

On August 18, 1945, Pu Yi, China’s Last Emperor, who by that time was reduced to being the emperor of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, renounced his throne and prepared to flee northeastern China along with the defeated Japanese Army. Bernardo Bertolucci’s Academy Award-winning film, ‘The Last Emperor’ depicted the moment when Soviet troops seized a Manchurian airport and stopped Pu Yi and his royal entourage from escaping to Korea. They were taken to the Soviet Union to meet an uncertain fate.

In ‘The Last Manchu: The Autobiography of Henry Pu Yi, Last Emperor of China,’ he dedicated a chapter to his time as a prisoner in the USSR. There is very little information in the Russian public domain about Pu Yi’s life in the country, making this book an important source of information about this little-known part of history.

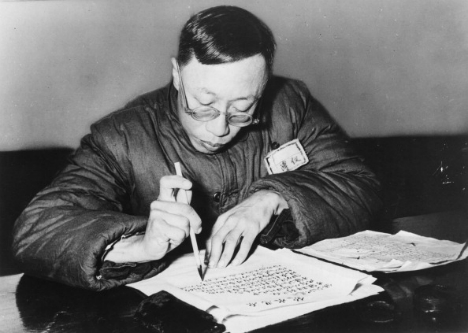

Puyi in prison. Source: Getty Images

According to the book, right after his plane landed in Siberia, Pu Yi was put in a sedan and driven for hours before the car stopped. He feared for his life when someone told him in fluent Chinese that he could step outside and urinate if he wanted. “In the darkness, I became frightened,” he wrote. “The voice made think that some Chinese had showed up to take us back to China, and if this were true, I would without doubt be killed.” The man who spoke in Chinese turned out to be a Soviet Army officer of Chinese descent. Not only was Pu Yi’s life not in danger, but as he described in the autobiography, he lived in Chita and Khabarovsk over the next five years in relative comfort.

His first stop in Russia was a Soviet sanatorium or resort near the Siberian city of Chita, which was famous for its mineral springs. “We had three square Russian meals a day as well as afternoon tea, Russian style,” Pu Yi wrote. “There were attendants to look after us and doctors and nurses, who constantly checked up on our health and took care of us when we were ill.” The Soviet authorities provided him with books, board games and a radio. He also took regular walks, enjoying his life in Chita.

In 1945, it was still unclear as to whether the Nationalists loyal to Chiang Kai Shek or the Communists would win the Civil War in China. This was the main reason why the USSR was in no hurry to return the former emperor back to China.

Pu Yi was also not aware of the global geopolitical situation that was developing at that time. “Not long after our arrival, I developed the illusion that since the Soviet Union, Great Britain and the United States were allies, I might be able to move eventually to England or the United States, and live the life on an exile,” he wrote. The former emperor had enough jewelry and art objects to live out the rest of his life in the West.

He believed that the best way to achieve this goal of living in the West was to make sure that he could initially remain in Russia. The former emperor even wrote to the Soviet authorities thrice to seek permission to live in the country permanently. Convinced that both the Nationalists and the Communists in China wanted to kill him, he tried in vain to convince the USSR to let him stay for good.

Pu Yi was later moved to the city of Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East. From his own descriptions, the conditions were not as good as they were in Chita, but he still lived a privileged existence. He seemed irked that the other prisoners could no longer call him “Emperor” or “Majesty” and stuck to calling him “Master Pu.”

“During my five years’ detention in Soviet Russia, I was never able to dispense with my prerogatives,” he wrote. In Khabarovsk, he didn’t have any attendants but co-prisoners, including his family members would wait on him. His family members, who would bring him his meals and wash his clothes, referred to him as the “Upper One.”

A still from The Last Emperor. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

He wrote about the inconveniences he experienced when the Soviet authorities moved some of his family members to another center. The former emperor’s brother-in-law then brought him food and washed his clothes.

Despite his attitudes towards doing things himself, Pu Yi cultivated a passion for gardening and started growing vegetables in a plot of land that was allotted to him. “My family and I raised green peppers, tomatoes eggplant, beans, and other vegetables, and when I saw how these green plants grew daily, I was most impressed,” he wrote. A love for gardening was something he would carry with him to China. After he was released from a Chinese prison, this was his profession of choice.

For Pu Yi and his co-prisoners, the only sources of news from China would be their interpreters and a Chinese-language newspaper published by the Soviet Army in Port Arthur called Trud. Going by the former emperor’s descriptions of his life in the USSR, the authorities did not demand too much from him. They offered Soviet Marxist and Leninist books, but he was bewildered as to why they would want him to read the books if he was not going to allowed to stay permanently in the country.

In 1946, the Soviet authorities took him to Tokyo to testify at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. “I accused the Japanese of being war criminals in an utterly direct and unreserved way,” he wrote. “However, whenever I spoke about this period of history, I never discussed my own guilt.”

Pu Yi eventually donated some of his jewels and treasures to the Soviet authorities, claiming that he wished to support their post-war economic reconstruction. “Since the Soviet Union was the deciding factor in my life, it therefore was best to be nice to the Russians and seek to gain their favor,” he wrote.

In August 1950, Pu Yi was sent back to China, temporarily separated from his family and accompanied by Russian officers. “Although they had joked with me and given me beer and candy, I still felt that they were sending me to my death,” he wrote. The Last Emperor would live for another 17 years, and even witness the beginning of the Cultural Revolution.

After ten years in a prison, where he was declared reformed, PuYi worked in the Peking Botanical Gardens. He even won favor with Mao Zedong, who encouraged him to write his autobiography.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox