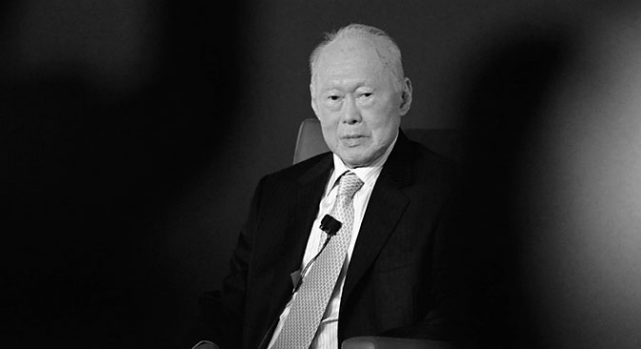

Source: EPA/Vostock-Photo

It’s OK to be jealous of Lee Kuan Yew. The late Prime Minister of Singapore was the hero of the ultimate country-sized success story. For any leader of the developing world, the title of his political testimony – From the Third World to the First – represents a headline for the biography of their dreams. Southeast Asian politicians will look up to Lee as one who was able to use a firm grip on power to make a powerhouse out of a sleepy city-state, making it a shining example of post-colonial development.

As cheesy as it sounds, this is the end of an era. Ironically enough, this era, in which economic growth and industrialization have been at a premium for Southeast Asia, may soon be remembered as the easy one. Due to many reasons often presented by observers of the Singaporean story, the country has actually been the only one in the region able to push through the middle-income trap straight into the high-income zone. All the others, some barely there, will probably be staying in this development limbo for a long time.

Modernization is far from over for Southeast Asia. It’s not just about the economy, but about making the political systems flexible enough to withstand power transitions, legitimacy crises and social shocks. Political reform has been lagging behind growth for some time now, but in 2014 the region has seen a series of unfortunate events and trends even dubbed ‘democracy under siege’.

In Malaysia, a return to power of the Barisan National party has raised the question of trust in the Electoral Commission. Prime Minister Najib Razak has proclaimed the country “the best democracy in the world,” but not all agree – the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked the country 65th in the Democracy Index, attributing a “flawed” description to the political system. Even less characteristic of a proper democracy is the 147th place occupied by the country in the 2014 World Press Freedom index – the lowest ranking Malaysia has ever received. All this comes against a background of growing concern over government policies biased towards Muslim Malays.

Meanwhile, Myanmar’s reforms are under threat yet again. The process was rather slow to start with, but the gradual advance of political ‘demilitarization’ has hit a rough patch this year. Ongoing turmoil in Kokang and Rakhine are reinforcing hardline rule, stalling the political transition towards a system that would foster stable FDI flow and provide a favorable environment for business, as well as ensure better popular representation.

And that is just the beginning. The 2014 military takeover in Thailand is not as temporary as many may have hoped and is likely to annoy Bangkok’s partners on the other side of the Pacific. In Indonesia, the charismatic Joko Widodo has seen his approval rating slide from 71 to just 42 percent – a trend that may affect the leader’s freedom to upgrade local and national connectivity and improve living standards.

All across the ASEAN, leaders are struggling to address lack of infrastructure, weak institutions, low-quality legal frameworks, income disparity, ethnic diversity and rampant corruption. The latter requires special attention. It has become almost common knowledge that rapid development is always accompanied by graft as more and more value is produced and only a relatively small social group has access to the distribution of this value. Some even claim that government officials are more likely to promote business opportunities exclusively if they have a chance to reap their own private benefits, making a case for tolerating corruption for quite a long time.

Though there is a certain truth to that, it’s hard to deny that corruption hurts the economy in the long run. As nepotism and graft become ingrained in the system, reform becomes increasingly difficult. Take Vietnam, for instance, an economic-miracle-to-be where much anticipated market reforms encounter resistance from civil servants elbow-deep in the state-owned enterprises they are supposed to regulate.

Now here’s an issue the late Lee Kuan Yew managed to tackle with outstanding virtue, inviting neighboring states to follow his example. The Singaporean Story is certainly special: It has a unique setting and unique characters, including the main protagonist. But the tasks at hand for other leaders of the Western Pacific are as monumental as the ones Lee faced. A new consensus needs to be found – one that could be as comprehensive as Lee’s, transcending political culture and economic development. New challenges lie ahead and a new hero is needed. Perhaps we will soon be reading someone else’s story. In the meantime, let us return to Lee’s and be a little jealous.

Anton Tsvetov is the Media and Government Relations Manager at the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC). Read Anton Tsvetov's blog here.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox