Nikolai Kochergin, 1940. Don Cossacks capturing the fortress of Azov, 18th July, 1837. Source: Fine Art / Vostok Photo

Theirs was a long journey. At the end of the 16th century, the Cossacks’ ancestors, the peasants of central Russia and Ukraine, fled from serfdom and religious oppression to the lower reaches of the Dnieper and Don rivers. Here they organized themselves according to military democracy, without set rulers and masters, true to the essence of their name: Of Turkic origin, the word Cossack means ‘free’.

But freedom must be protected, so the education of a Cossack was primarily military. Yesterday's peasants learned to deftly handle edged weapons and firearms, build small ships and throw up and defend fortifications against their many enemies.

They were constantly threatened by Poland along the lower Dnieper. Every summer Polish troops tried to clear the Cossacks from fortified islands in the river, drawing devastating retaliatory raids on the estates of the Polish gentry. Another constant threat was Turkey and its vassal, the Crimean Khanate. And Don Cossacks also fought against the mountain folk of the Caucasus and the Persians.

It was in these battles that the classic Cossack warrior was forged, superior to any enemy, whether on foot or horseback. Neither the elite Turkish janissary infantry nor the Polish hussars could outdo them in strength and ability with weapons. Cossacks were also skilled at operating in fast-moving groups, but also adept at defending fortified positions.

In the mid-17th century several thousand Don Cossacks successfully defended the fortress of Azov (in today’s Rostov Region - RBTH) for five years against a Turkish force several times larger. But what they lacked was organization. Unaligned they could not survive indefinitely in encirclement. Their strength was in their impetuosity and personal courage, but this could never win at length against large armies of regular troops. Militarily, the Cossacks required more infrastructure, including factories and workshops for casting guns and making muskets.

So by the 17th century most Cossack villages had come under Russian rule. The tsars made a special contract with them, whereby they were given land but in turn had to serve in the Russian army and protect the country’s southern borders.

Mounted Cossacks were indispensable in repelling attacks by nomads, who encroached on Russia’s central regions until the end of the 18th century. Being able to easily intercept the Tatar hordes and attack Crimean and Nogai (a Turkic tribe from the Caspian steppe and North Caucasus - RBTH) encampments, they also adopted many combat techniques from the Tatars.

One was the trademark shrieking horseback charges on enemy villages while wielding two swords instead of holding the reins. Caucasian highlanders also taught them the tricks of dzhigitovka riding, in which the rider leaps from his horse at full gallop, or slings himself beneath its belly to snatch objects from the ground.

Today the equestrian art of dzhigitovka is still practiced as a sport by the distant descendants of the Cossack warriors. But three centuries ago it was a honed military technique that enabled riders to dodge bullets and arrows and attack the enemy where least expected.

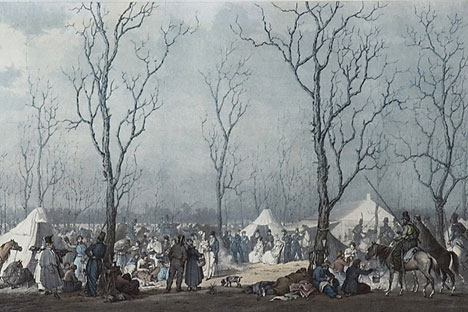

Vasily Timm, 1851. Cossack camp on the Champs Elysees in Paris 19-30 March 1814. Source: Fine Art / Vostok Photo

Europe first came up against the steppe horsemen of the Russian tsars in the early 18th century in the Northern War against Sweden. It made little sense to use Cossacks against regular Swedish cavalry, but they proved indispensable in reconnaissance and guerrilla warfare. Sweeping like a whirlwind through the rear of the Swedish army, Cossack raiders wiped out entire enemy units, took prisoners and destroyed supplies.

But they could show firmness in restraint too. In 1760, Cossacks came to Berlin in the ranks of the Russian army that defeated Prussia. They were put to policing the streets of Berlin, and fulfilled the task admirably.

Their fighting peak came in the 1812-1814 war against Napoleon, in which over 40,000 Don horsemen battled the French army. The first clashes showed that the invaders were dealing with a formidable opponent. On 27-28 June, 1812, around 4,500 Cossacks routed the French cavalry at Mir in Belarus, using Tatar ambush techniques to ensure an epic victory.

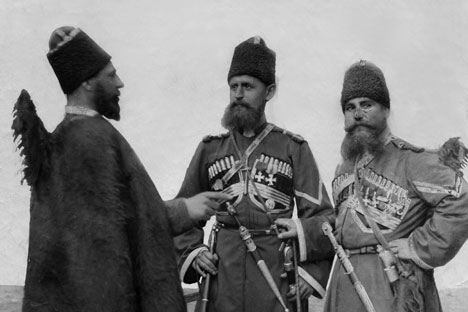

Russian cossacks, 1905. Source: Ullstein / Vostok Photo

After the Polish cavalry of the French forces drove back the Russian vanguard and stormed Mir, Cossack cavalry cut unexpectedly into their rear to ensure a crushing defeat. The Cossacks attacked in a ‘lava’ formation, in which the horsemen function in a molten mass with no regulation, apart from basic interaction with the nearest riders, enabling each to function independently and to the greatest effect.

In the battle of Borodino, as Russian troops began to dominate the central ranks of the French, a Cossack lava rush swamped the enemy’s left flank. Taken unawares, the French abandoned their weapons and guns and retreated, allowing the Russians time to bring up their reserves.

The Cossacks triumphantly entered Paris in March 1814, broke camp on the Champs-Élysées and proceeded to make an indelible impression on the Parisians during their two-month stay.

Their appearance and habits made them a star attraction in the city, as the Cossacks cooked over roaring fires and stripped naked to bathe their horses in the Seine, all with discipline and order. French propaganda that had for years portrayed Cossacks as child-eating savages was spread to the winds, and the Parisians marveled at these fabled warriors who greeted them with courteous bows on the streets and even visited their museums.

Cossack cavalry served in the Russian army for more than 100 years. Their units were instrumental in the wars against Turkey and Japan, won glory in the First World War and fought with distinction on both sides in the Civil War.

Soviet cossacks and UK soldiers meet each other on the Elbe River, on April 25, 1945. Source: ITAR-TASS

And in 1945, Cossack forces entered Berlin with Russian units for the second time in their history.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox