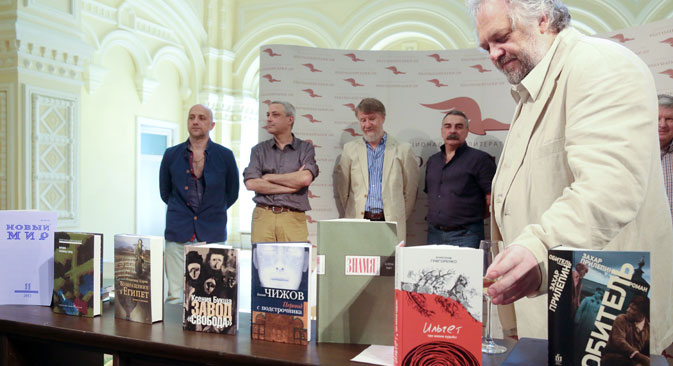

"The Big Book" prize finalists (from left to right) Zakhar Prilepin, Yevgeny Chizhov, Vladimir Sharov, Viktor Remizov and the prize expert Mikhail Butov at the shortlist announcement ceremony. Source: ITAR-TASS

The jury traditionally selects between eight and 15 books for the shortlist. This year’s shortlist has nine titles, chosen out of a long list of 29:

1. Svetlana

Aleksiyevich – “Time Second-Hand”

2. Kseniya Buksha – “Svoboda Factory”

3. Aleksandr Grigorenko – “Ilget”

4. Aleksey Makushinsky – “Boat for Argentina”

5. Zakhar Prilepin – “Cloister”

6. Viktor Remizov – “Free will”

7. Vladimir Sorokin – “Telluria”

8. Yevgeny Chizhov – “Translated from Word-for-Word Translation”

9. Vladimir Sharov – “Return to Egypt”

Experts are tipping Zakhar Prilepin’s “Cloister” as the favorite to win the prize. This history of the ancient monastery of Solovki, which was turned into a prison in the 1920s, is told from the point of view of a young man who ended up there for an accidental murder.

“In this novel, Prilepin has reached new heights in terms of his writing and understanding of life,” says Mikhail Butov, chairman of “The Big Book” prize’s board of experts.

“Yet, what is more important is that the book raises the always topical subject of a spiritual feat that a human being achieves against the backdrop of political reprisals and a struggle for survival. It is not only Russian readers who understand and appreciate this subject.”

Kseniya Buksha’s novel “The Svoboda Factory” is also set in the 1920s and depicts that initial period of the Soviet state’s development through the eyes of employees at a defense plant.

The book is based on the author’s interviews with workers at a St Petersburg plant and even contains their direct speech. Yet it is a work of fiction in the now almost forgotten “industrial novel” genre.

A similar method is used by Svetlana Aleksiyevich, who was tipped for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013 and has received numerous awards, including the Herder and Remarque prizes.

Her novel “Time Second-Hand” uses different voices to tell the story of Soviet life, which did not end with the breakup of the USSR. This is a documentary text made up of first-hand accounts, confessions, interviews and dinner discussions.

“Literature can be like that too. Aleksiyevich’s books can teach you the history of our country better than any history textbook,” Butov points out.

“One can agree with Aleksiyevich or disagree with her; one can argue with her or reject her, but she is a writer that always causes a reaction in her readers.”

Two of the most elaborate novels on this year’s shortlist present characters that deal with the intricacies of Russian history. In Vladimir Sharov’s epistolary novel “Return to Egypt,” a Soviet agronomist by the name of Nikolai Gogol, who is a descendent of the great Russian writer of the same name, is trying to write a sequel to the classic novel “Dead Souls.”

However, the book is not about Gogol; it follows the journey of Soviet generations whose lives are correlated to the Book of Exodus in the Bible – hence the novel’s title. According to Butov, Sharov “is one of the most difficult Russian authors but also one of the most interesting. If others only feel bold enough to experiment once in a while – for him, all his work is an experiment.”

Readers will be equally challenged by Aleksey Makushinsky's “Boat for Argentina,” written in the tradition of European modernism. Makushinsky is the son of the Soviet writer Anatoly Rybakov, who was a victim of Stalin-era reprisals.

In the novel, Russian history is intertwined with European history, while Makushinsky can compete with Proust in terms of the complexity of his language – and is just as difficult to translate.

An alternative history of Russia is a favorite theme in Vladimir Sorokin’s works. His “Telluria” is a dystopian tale of Russia plunged back into an age of warring fiefdoms. Sorokin is a master of style, and in this work he has written each of its 50 parts in language reflecting the different mentalities of the citizens in his imaginary future Russia.

Despite all the variety offered by the 2014 shortlist, Mikhail Butov points out that this year, perhaps for the first time, he can answer journalists’ favorite question: would it be fair to say that there is a specific trend in this year's literature? “It would!” he replies.

“The 2014 Big Book shortlist has shown that the traditional novel is enjoying a comeback in Russian prose. Long, complex, raising the fundamental issues of life – in other words, the type of novel that Russian literature has always been famous for.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox