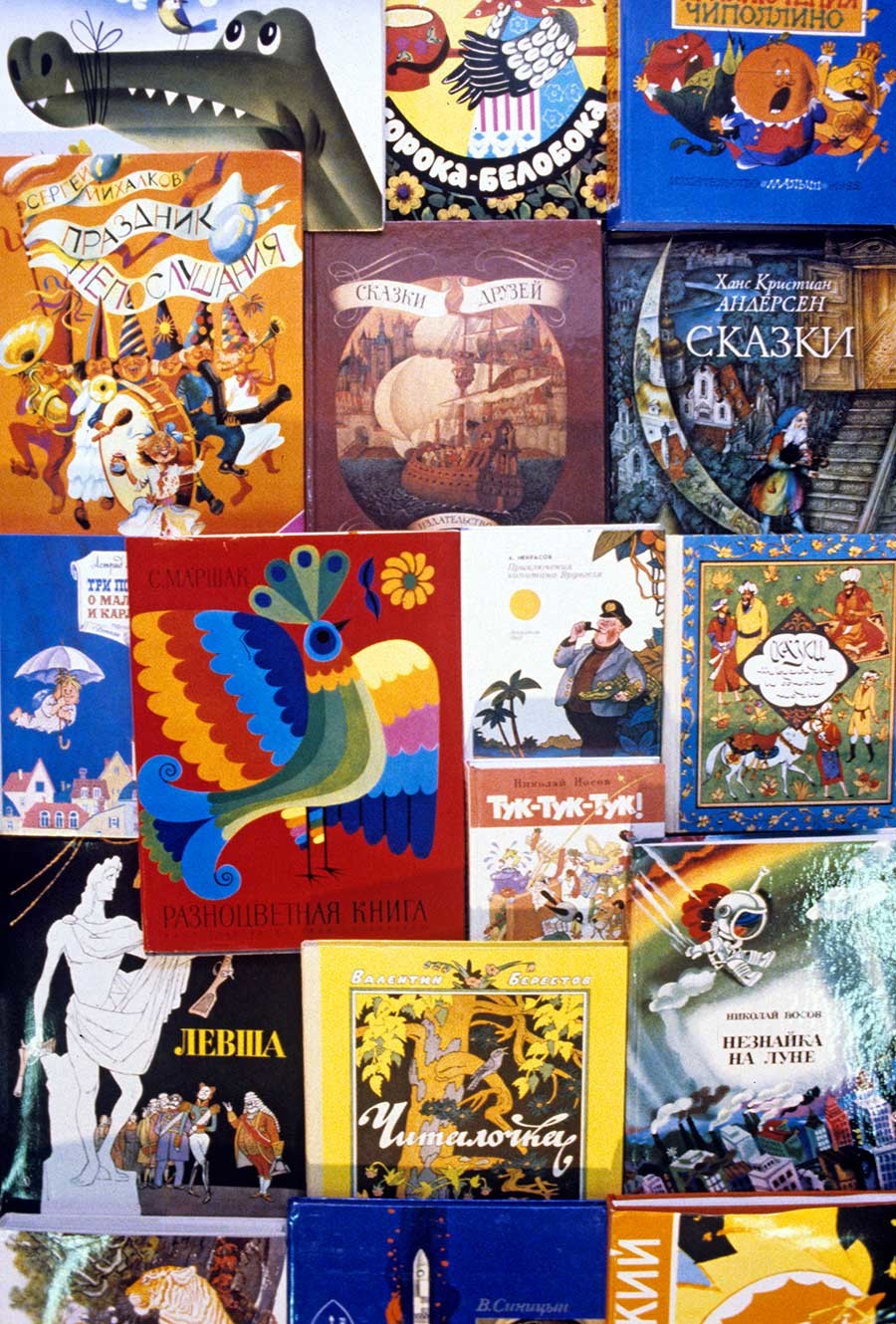

Most of Soviet book for children are still very popular among parents and their small kids

TASSThe new Bolshevik government was quick to identify the potential for children’s literature as a tool to spread its ideology to the new generation. This left writers vulnerable to the censor’s whims, which tended to lurch from one extreme to another.

Sometimes the government wanted to attack family values, which were perceived as an obstacle to a true socialist education. When this happened, materials that depicted family life in an overly positive light were not published. Other times, the militant materialists turned their attention to fairy tales, as these works left room for magic, and it was deemed inappropriate to fill a Soviet person’s head with such nonsense. Nadezhda Krupskaya, Vladimir Lenin’s widow, was one of the most ardent opponents of fairy tales.

In 1933, the authorities took full control of children’s publishing houses. The state gave unprecedented support to children’s literature, and the authorities demanded ideological loyalty in return for investing significant resources into this area.

An important voice in these early years belonged to Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), a writer who was passionate about establishing a common culture and artistic taste. Gorky was revered for his moral authority by both the government and the general public and helped shape a vision of children’s literature that was not overly ideological and dull.

In 1933, Gorky published an article entitled “Literature for Children” in the Izvestia newspaper, where he claimed that books “should promote the development of interest in art and knowledge among children … familiarize them with the old reality destroyed by their fathers and with the new reality that will be built for them by their parents.”

However, he went on to add: “It isn’t necessary to think that literature should be created for the sole purpose of education. We also need cheerful, funny books that help to instill a sense of humor in children. Preschoolers need simple yet artistically developed poems that serve to provide a foundation for games.”

Samuil Marshak (1887-1964), the first chief editor of the State Children’s Publishing House (Detgiz), shared Gorky’s values. The brilliant translator and poet adhered to the motto “big literature for the little ones,” and he hated sloppy work. He wanted to allow only the most talented individuals to write and illustrate children’s literature.

In 1933, the authorities took full control of children’s publishing houses

RIA NovostiKorney Chukovsky (1882-1969) is commonly considered to be the father of “the new era of children’s books.” He was known primarily for his poetic tales, which served as the introduction to the world of literature for many people. In Soviet times, millions of copies of his books were published, and his dacha outside of Moscow became a place for endless school trips and visits by novice writers. Chukovsky’s success has not decreased with time. According to the Chamber of Books, over 2 million copies of his books were published in 2013 alone, making him still the most widely published children’s author.

Chukovsky was self-taught; he worked his way up from the bottom rung of society to become a brilliant critic, philosopher, and translator. Much like JK Rowling, the idea for his first fairy tale came to him while he was on a train, and the success of his short poem “The Crocodile,” which was published in 1919, was comparable to the success of Harry Potter. It tells the story of a crocodile that roamed the streets of Petrograd and combined with other animals to raid the zoo and free their friends.

The secret to Chukovsky’s stories is that they speak to children in a language that is cheerful and easy to understand. They are genuine, lively, dynamic, playful, bold – and never fussy. Chukovsky was a father of four and understood children’s needs. He treated them with respect and described them as “the most creative people of all mankind.”

In his book “From Two to Five,” Chukovsky discusses child psychology. He presents a host of children’s phrases and analyzes them. He looks for patterns in language development and illustrates the specifics of children’s perception.

Nikolay Nosov (1908-1976) is still actively republished to this day. The heroes of his books, “

In “Neznayka on the Moon,” the heroes come across a capitalist society, where they are introduced to the latest innovations in science and technology. The political context, however, was of little importance to children. But, along with the

These are just a few examples. There are dozens of wonderful Soviet-era children’s writers and poets.

'Aybolit' by Korney Chukovsky

Fairy tales in the form of poetry and prose about the great Doctor Aybolit, who is prepared to set off on long and dangerous journeys in order to help his patients – both children and animals. The author readily admitted that Aybolit was based on the story of Doctor Dolittle by Hugh Lofting. The plot of Aybolit is not tied to any particular era: it was as popular in the 1980s as in the 1930s.

“The Little Gold Key, or the Adventures of Buratino” by Alexei Tolstoy

Buratino was Pinocchio for Soviet children

RIA NovostiAlthough the author of Buratino was not a children’s writer, he decided to modify Carlo Collodi’s famous fairy tale about a wooden boy called Pinocchio for Soviet children. However, the end result was far more than just an echo of the original – it was a completely different fairy tale that was more adventurous, fun, and better suited for a socialist state. In the story, the wooden boy learns how to read, along with good manners and the important life lesson that wealth can only be acquired through hard work.

Soon, Buratino and his friends – a poodle called Artemon and a girl called Malvina – became so well known among Soviet children that they were practically considered Russian. Buratino became a brand name and has been used in a number of different spheres, from lemonade to rocket launchers.

Children’s Poems by Agniya Barto

Barto was popular thanks to the genius simplicity of her poems, which were easy to memorize after just one reading. Their main characters are simple archetypes with typical Russian names such as Tanya,

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox