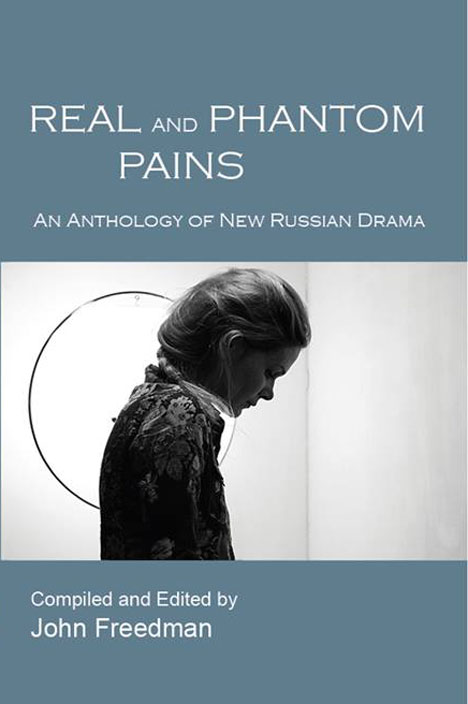

Source: New Academia Publishing, 2014

A 500-page collection of contemporary Russian drama, “Real and Phantom Pains: An Anthology of New Russian Drama,” has just been published in the United States. The volume contains 12 plays. John Freedman, the book’s editor and a theater critic and culture expert, sat down to talk about the book’s target audience and why the Anglophone world is interested in Russian theater.

John Freedman: I chose plays without which I couldn’t imagine Russian theater existing for the last 14 years. Russian drama has experienced a true golden age throughout the 2000s. I am convinced, for instance, that the history of Russian drama is impossible without Olga Mukhina. Her play “Flying,” which is in the collection, was the first play about the reality of a new social class in Russia: office workers. The play has been staged frequently in the United States, Europe and the Russian provinces, yet in Moscow it has not received the attention it deserves.

It goes without saying that this list must include Maxim Kurochkin’s “Kitchen” and Pavel Pryazkho’s “Panties” – these are milestone works of “new drama.” And Vasily Sigarev is extremely popular in Europe and America. I would hazard to say that for many in the world today Sigarev is Russian drama. For my collection I chose “Phantom Pains,” maybe not his most famous play, but it is as harsh and compelling as anything he has written. I think it has every chance of being staged in the U.S. On the whole, I think the anthology gives a fairly precise picture of what has happened over the period that it covers.

Izvestia: In your book, nearly all the authors are well-known and acknowledged leaders of the “new drama,” with the exception of Maxim Osipov.

J.F.: Osipov is a rising star. I guarantee that you’ll be hearing his name a lot. He’s a doctor by training, like Chekhov, Bulgakov and Veresaev. He didn’t start writing and publishing stories until he was over 40, and he was immediately successful. I included his play “Scapegoats,” which, on one hand encompasses all the distinctive, topical themes of “new drama,” but does so in the context of the great Russian literary tradition. In my opinion, “new drama” and contemporary Russian drama are not the same thing. “New drama,” for all its importance, is just one part of the contemporary drama scene.

Izvestia: What is this book’s target audience?

J.F.: I want theaters, directors and actors to take notice of Russian drama. I wouldn’t want it just to be studied in universities. I want these plays to be produced and to enter the repertories of American theaters.

Aside from that, I think the book will also interest people who want to get a feel for contemporary Russian reality. Everyone reads and admires Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, but few people understand what is going on in Russia now. Foreign stores sell books by Pelevin and Sorokin, but this obviously isn’t enough.

An anthology of plays is an ideal option. A play is short, like a small epic poem. You can breeze through it in 30 or 40 minutes. All the plays are very different and about different things, but taken as a whole they give a multifaceted picture of modern Russia.

John Feedman and his wife, Russian actress Olga Mysina. Source: PhotoXpress

There are also personal motives behind this book. I’ve lived in Russia for 25 years and I consider myself a Muscovite. Rationally and factually speaking I’m from America, but my heart has long belonged to Russia. These two countries presently find themselves in a very difficult, tense period, one full of discord. So for me it’s especially important to remind people of Russia’s rich culture, and, in so doing, perhaps to bring Russia a bit closer to America, and America a bit closer to Russia. Let’s just say this is my small contribution to the fight against the political madness we see these days.

Izvestia: The plays of the “new drama” focus on Russian reality. Were you able to make the texts understandable to the English-speaking reader?

J.F.: I can only answer for the eight plays I translated myself (the other four were translated by friends and colleagues, who did an outstanding job). For one thing, I speak the language fluently and I know well the reality of Russian life. My wife, the actress Oksana Mysina, is always by my side and willing to help if necessary. I know all the authors in the collection and it is easy enough for me to ask them for clarifications at any time.

However, there are always problems in translation. There may be something I understand myself, but which needs a small explanation or an expanded translation in order for American readers to make sense of it. Sometimes it’s a matter of choosing a creative equivalent. For example, in Osipov’s “Scapegoat,” the hero quotes the romance “Farewell, Happiness, My Life,” which was famously sung by Chaliapin. I replaced this line with a quote from Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bye-Bye, Love,” a song virtually every American knows well.

I tried to make things comfortable in places for Western readers so that they wouldn’t be put off by unfamiliar or unexpected actions, situations or turns of phrase. You want to draw spectators in, rather than scare them off. At the same time, of course, you can’t go too far with American details. It’s a tightrope walk. You must preserve the spirit of the original.

Izvestia: In your opinion, what is the specificity of the “new drama”?

J.F.: Russian drama of the last few years is rich in treatments of difficult social problems. Each author is immersed in his or her own theme, but together the works reveal a broad panorama of the real and phantom pains of Russian society. In some way or another all the authors are trying to answer two questions: “Who am I?” and “Where am I?” After the fall of the Soviet Union, a flood of complex questions burst forth. Who am I? Soviet or Russian? How will I live in the new conditions? Compared to America and Europe, life in Russia is catastrophically unstable. It constantly provokes new questions that need to be answered.

First published in Russian in Izvestia.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox