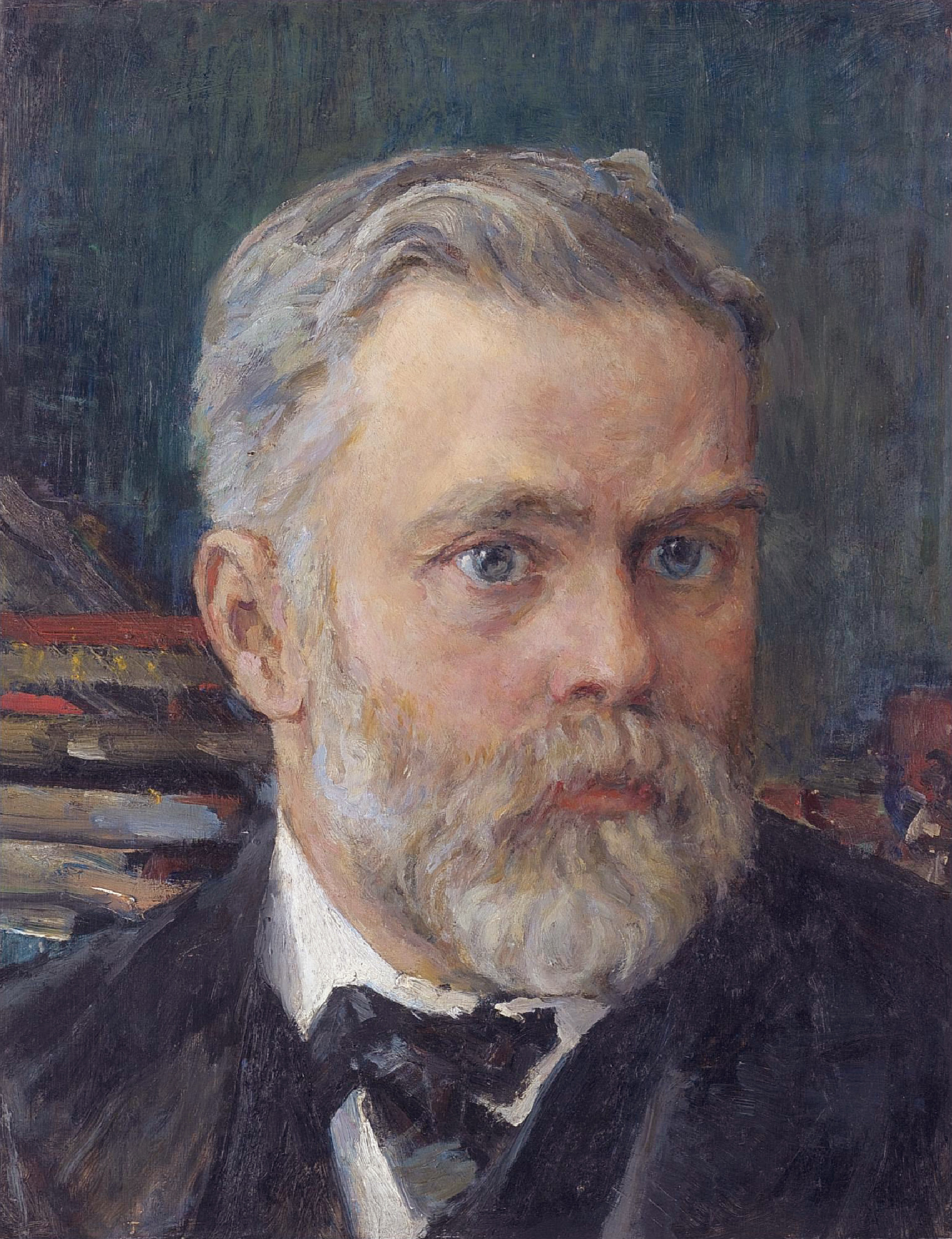

Emanuel Nobel, portrait by famous Russian artist Valentin Serov

Open sourcesThe important chapter that Alfred Nobel and his family wrote in Russian industrial history is not widely known, and neither is the family’s closeness to Ivan Bunin, the émigré Russian writer who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1933. Could they have influenced the result in the fierce battle between Stalin’s favorite Gorky and the

Immanuel Nobel moved from Sweden to St. Petersburg in 1838 with three sons, Robert, Ludwig and Alfred, who famously invented dynamite. The family proceeded to make a fortune developing the Russian arms and oil industries, among others.

By 1916, the “Russian Rockefellers,” as they were later called, owned, controlled, or had

But two years later, when the Bolsheviks took power, Emanuel had to flee Russia disguised as a peasant, while his two brothers were imprisoned by the Cheka secret police. The Nobel empire crumbled overnight as the refinery fires were extinguished, hundreds of wells were filled with water, the family factories in St. Petersburg were closed down, and their property was seized.

In exile for the next 10 years, first in Paris, then in Stockholm, the Nobel family fought through the courts to recover what had been seized by the Bolsheviks. Meanwhile, the Nobel family – particularly Emanuel Nobel – became dedicated to fulfilling Alfred Nobel’s will through the famous Nobel Prizes.

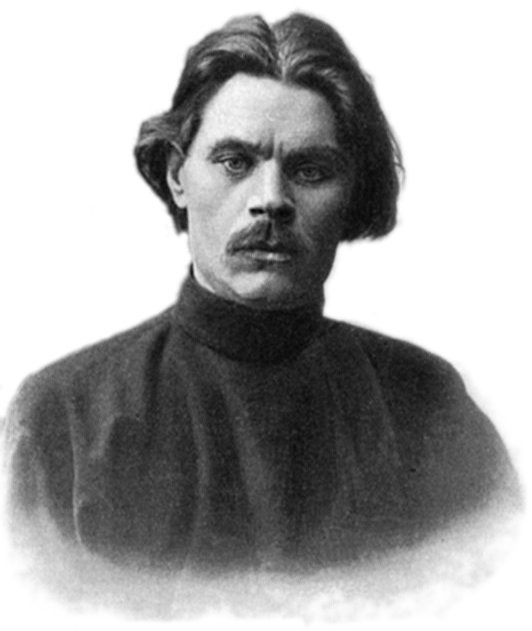

Maxim Gorky

Archive PhotoThe scene was set for the intrigue that developed over many years about who would be the first Russian to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. On one side were those in favor of Stalin’s favorite, Gorky, who had remained in the Soviet Union after the Bolshevik Revolution, while the other camp supported the émigré “white” writer, Ivan A. Bunin, an anti-communist who fled Russia to France in 1921.

Gorky had an international reputation and was supported by influential personalities in the literary world, including George Bernard Shaw, Gide, H. G. Wells and Stefan Zweig. And he was, before Bunin, a clear favorite for Nobel Prize when he was first nominated in 1918.

Bunin, however, became increasingly popular in the democratic West, particularly in France, with its well-established Russian émigré community. But the deciding factor in the race to become the first Russian winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature was perhaps the backing of three crucial figures.

During his Parisian exile, Emanuel Nobel had close ties with Russian émigrés,

Nobel was impressed by Bunin’s writing and befriended him, but he had no official influence over the Nobel Committee. Indeed, Solomon Volkov, a

Ivan Bunin

Archive PhotoRomain Rolland, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1915, was Bunin’s second important backer. Although the French writer, a “Friend of the Soviet Union” who had accused Russian émigré writers of “cultural and spiritual backwardness,” was a personal acquaintance of Gorky, he asked the Kremlin to support Bunin’s nomination for the Nobel Prize in 1930 and 1931. Moscow, however, was appalled at this prospect and started putting out other feelers through Alexandra Kollontai, the Soviet Union’s ambassador to Sweden. Stalin was very clear on one point: the first Russian to receive this prestigious award should be a proletarian writer, and Bunin did not fit that profile.

Bunin’s third key supporter was Thomas Masaryk, the first president of Czechoslovakia and an important patron of the Russian cultural diaspora. His government gave subsidies to exiled writers and supported several publications that were critical of the Bolsheviks. Bunin personally received direct financial support from Masaryk’s government as early as 1922.

On Nov. 9, 1933, while Bunin and Galina Kuznetsova – his secretary and mistress – were at the cinema, his wife, Vera Nikolaevna Bunina was told over the phone that her husband had been awarded the Nobel Prize. Bunin received congratulatory calls and telegrams from all over the world, but the official Soviet reaction, as published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, was cutting: “Unfortunately, instead of being awarded to our great proletarian writer Maxim Gorky, the Nobel Prize went to an inveterate enemy of our revolution.”

When Bunin, accompanied by Vera and Galina, went to Stockholm for the awards ceremony, he was received by Emanuel’s brother-in-law Oleinikoff and stayed at the Nobel family’s residence, a privilege that no other nominees enjoyed. Emanuel himself did not live to see his favored writer and fellow émigré become a laureate – he died in 1932.

Ivan Bunin received the award, in the words of The Nobel Committee, “For the strict artistry with which he has carried on the classical Russian traditions in prose writing.” Later, Dr. Anders Österling, a member of the Swedish Academy, allegedly made a more candid admission as to why Bunin was selected: “to pay off our bad consciences on passing over Chekhov and Tolstoy.”

Bunin died in 1953 – the same year as Stalin – and it was only after this that his books began to appear in the Soviet Union. However, it was not until perestroika that his works dealing with the October Revolution were finally published.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox