When you know the life story of Tolstoy's second daughter, Maria, you are particularly touched by her father’s words about her in a letter to his aunt, Alexandra Andreyevna:

“The fifth, Masha is two years old, the one whose birth nearly cost Sonya her life. A weak and sickly child. Body white as milk, curly white hair; big, queer blue eyes, queer by reason of their deep, serious expression. Very intelligent and ugly. She will be one of the riddles; she will suffer, she will seek and find nothing, will always be seeking what is least attainable.” [Translated by George Calderon for the book “Reminiscences of Tolstoy”]

The birth of Maria Lvovna Tolstaya (1871-1906) was the cause of the first serious conflict between Leo Tolstoy and Sofia Tolstaya. While breastfeeding one-year-old Lyovushka, Tolstoy's wife realized she was pregnant again, which she was not pleased about. She was tired of giving birth and breastfeeding; she was tired of feeling like a breeding animal rather than a woman. She then suffered from childbed fever after Masha’s premature birth, nearly dying. The doctors advised her against having any more children, but her husband was categorically opposed to this idea: he could not conceive of a married life without the birth of children, which nearly led to their divorce.

In his book “Tolstoy’s Children,” Sergei

Half-jokingly, half-seriously, people would say that Masha was suffering from a mental disorder encapsulated in the English phrase “as you like it.” In other words, you always do what other people want from you, rather than what you yourself want.

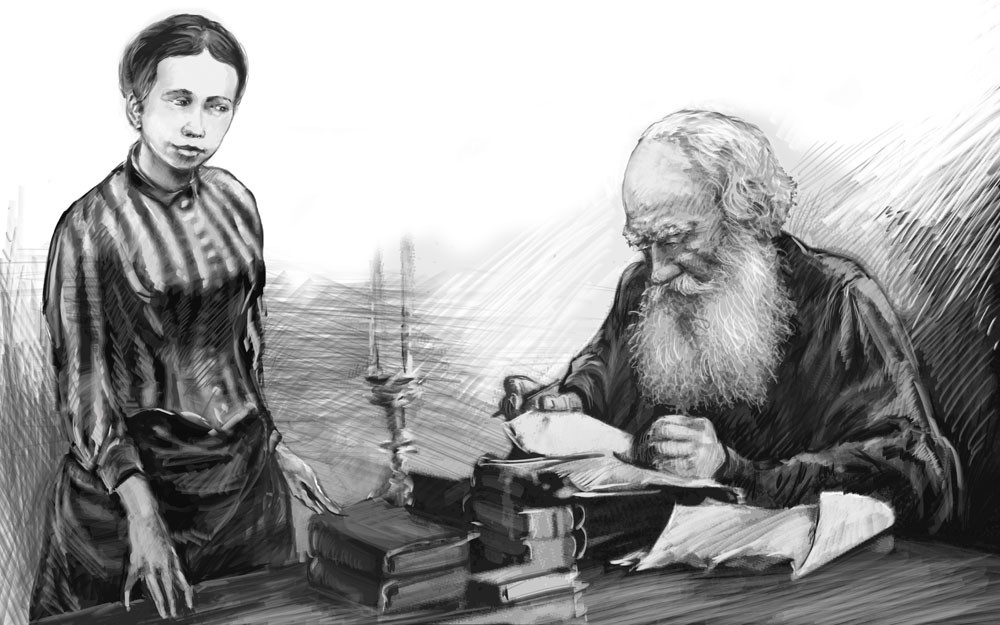

Maria followed Tolstoy everywhere like a shadow from a very young age. As a teenager she shared all his new views, renouncing her social life and becoming a strict vegetarian. She transcribed Tolstoy’s texts and managed his correspondence, serving as a link in all practical matters with his pupil and publisher, Vladimir Grigoryevich Chertkov. She often came into conflict with Chertkov, however, out of jealousy towards her father’s close relationship with him. For her part, Tolstoy's oldest daughter, Tatyana, was jealous of her father's close relationship with Maria.

Masha was the only grown-up child with whom Tolstoy could be sentimental, allowing her to be sentimental with him too. Lev Nikolayevich was never tender with his other children. This was largely due to Masha's nature: she was always sympathetic, cheerful, and always ready to help.

In addition to serving her father, Maria helped all the peasants on the Yasnaya Polyana estate. Intelligent, sophisticated, and fluent in several foreign languages, Maria made hay with the peasants, milked their cows, put out fires, re-roofed burned houses, taught the peasants' children to read and write, treated peasant women and delivered their babies...

The peasants adored her. Indeed, there was probably not a single person who would not have been charmed by her; she may not have been outwardly beautiful, but she had an incredibly beautiful soul.

Although she had given up

And yet... her story was similar to Tatyana’s. No matter how hard she tried to renounce her feminine nature for the sake of serving her father and ordinary people, nature prevailed. Her first love interest was Pavel Ivanovich Biryukov, a follower of her father and exceptional person who was much loved by the Tolstoy family. They seemed to be heading quickly towards a marriage that many people were certain would happen. However, Tolstoy refused Biryukov and talked his daughter out of marrying him. We can safely assume that he was afraid of losing a valuable assistant.

Masha’s second serious love interest was Petya Rayevsky, the son of Tolstoy’s friend Ivan Ivanovich Rayevsky. But Tolstoy was adamant this time too. “Has the whole world been reduced to this one person for you?” he wrote to his daughter. “From the outside, I can see that this one person is blocking the world from you, and the sooner he leaves, the brighter and better things will become for you.”

Masha’s third suitor was a modest music teacher, Nikolai Zander. He too received a definite, albeit polite, letter of refusal from Tolstoy. Apart from everything else, Zander was below Masha in terms of his social background. However, this time Maria was obstinate. She did not refuse Zander straight away and continued to see him in secret, much to the horror of her father, who could not believe it. The affair ended when the 26-year-old Masha fell in love with her father’s grandnephew, Prince Nikolai Leonidovich Obolensky, the grandson of Tolstoy’s sister, Maria Nikolayevna Tolstoy. Despite being a prince, Obolensky was almost penniless, but he was a kind man and he loved Masha. They could have been happy together, but she shared her sister’s fate on this occasion too: one after another, she gave birth to stillborn babies. Sofia Andreyevna was convinced that her daughter kept losing babies because she was a vegetarian, while her mother-in-law, Yelizaveta Valerianovna Obolenskaya, maintained that Masha had ruined her health “with unbearably hard work in the fields on a par with the peasants; once, during a fire in the village, she stood waist-deep in water passing buckets…” Whatever the truth, Maria could not give birth to a healthy baby. …

Her father had an astounding attitude to Masha’s predicament. Naturally, he felt sorry for his favorite daughter and tried to console her, but he chose a strange way of doing so. For example, after yet another failed birth, he wrote to her: “Sad as it is in a material sense, it is clearly a benefit for your spiritual life…”

In 1906 Masha died of pneumonia at the age of 35. She died in her father’s arms, who did not leave her bedside.

Pavel Basinsky is a Tolstoy scholar and the author of several bestselling biographies, including “Leo Tolstoy: Flight from Paradise,” which won the Big Book Prize.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox