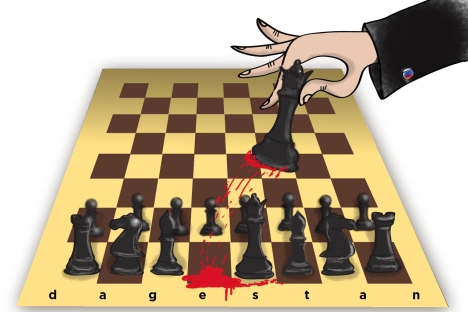

Drawing by Niyaz Karim. Click to enlarge the image.

The detention of Makhachkala Mayor Said Amirov has brought Dagestan into the spotlight once again. A veteran Dagestani politician has been taken out of the game in a move that is nothing short of sensational.

Dagestan has been the stage for many conflicts in the post-Soviet era. The largest and most populous republic in the North Caucasus, it is crossed by a number of demarcation lines that split its population along ethnic lines (Dagestan is one of the most ethnically diverse republics in Russia) and religious divides (proponents of Sufism, moderate Salafis and radical jihadists can all be found here).

Makhachkala has also been the battleground for several bureaucratic clans fighting for power within the republic, as well as for local officials and “Moscow Dagestanis” (businessmen and politicians of Dagestani origin who have settled in the Russian capital) competing for influence there.

Until recently, Moscow preferred to stay out of such disputes, as Russia’s federal authorities sought to maintain the status quo that is based on informal ties and a complex system of unwritten agreements. The arrest of Amirov, however, is a radical departure from established tradition.

Amirov was more than simply the mayor of Makhachkala – he was one of the key figures in the republic’s power structures. He had personal connections with the country’s top political leaders, a large business in Moscow (in defiance of his public duties in Dagestan) and enough gravitas to influence some of the most important managerial decisions outside his purview.

Amirov’s administrative leverage was complemented by his military and law-enforcement resources. To illustrate this, Amirov sent a squadron to support the federal government during a raid in Dagestan, which was undertaken by the militants Shamil Basayev and Emir Khattab in 1999.

Dagestan has 13 main nationalities, with Northeast Caucasian ethnic groups making up 77 percent of the population, according to a 2010 census. Avars (29 percent) are the most populous group, followed by Dargins (17 percent). Turkic peoples make up 19 percent, while ethnic Russians are just 4 percent.

The aid provided by Amirov and other regional “barons” was an important element in Russia’s success in preventing the further spread of the separatist cancer.

Later, Amirov played a significant role in helping the Russian ruling party, United Russia, establish itself in Dagestan.

Amirov has not only occupied his post for many years, but he has also received a number of high-profile government awards, as well as public support from the country’s leaders — before the situation changed earlier this year.

It would be a mistake to view Amirov’s arrest independently of other developments in the country. Having appointed Ramazan Abdulatipov to a public post at the beginning of this year, the federal government is now trying to strengthen the administrative standing of its protégé.

Without strong support from Moscow, Abdulatipov’s effectiveness would be reduced dramatically.

In addition, in the run up to the Sochi Olympics, next February, Moscow is concerned to minimize the risks associated with Dagestan, which has been the target of more terrorist attacks and various subversive actions than any other Russian republic in the last eight years.

Even though the willingness of the Russian authorities to safeguard themselves is understandable and justified, their actions could expose the country to certain threats. Even if Amirov’s case falls apart before it proceeds to court, he will most likely lose his job as a mayor anyway, and with him will collapse his existing clientele network, every piece of which will be fiercely fought over after its demise.

Then there is the question: Who will take over Amirov’s job as mayor? This is a serious question: Are Abdulatipov and his patrons in the central government ready to go beyond a mere change of door nameplates and start revising the rules of the game?

Of course, Amirov’s arrest may serve as a chilling warning to Dagestan’s bureaucratic clans and make them tame their appetites – at least, to some extent. However, we should also be mindful of the fact that most problems in Dagestan are related to systemic institutional problems. These issues cannot be solved by arresting people and putting them behind bars in a spectacular fashion; the likes of Amirov did not come into prominence by chance.

They became needed when Dagestan was left with almost no support, and had to find a way to deal with the separatist Chechen republic (the self-styled “Ichkeria”) on its borders.

Back then, Dagestan also needed to sort out the Lezghin issue in the newly independent Azerbaijan and find a solution to the situation with the resettlement of Qvareli Avars from Georgia — not to mention the problems brought about by property privatization and the transition from the Soviet planned economy to a new economic model.

It seems unlikely that the arrest of Amirov or any other government official could rid Dagestan of its high unemployment rates and overpopulation, or put an end to the painstaking urbanization that swells cities, empties mountain villages, erodes boundaries between ethnic communities and provokes conflicts.

It would be naive to think that any arrests could make the people of Dagestan forget their religious leaders and start listening to government officials, the police, prosecutors and judges.

Sergei Markedonov is a visiting fellow of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Ramazan Abdulatipov, 66, an ethnic Avar, was appointed acting head of the republic of Dagestan in January 2013 by President Vladimir Putin. Abdulatipov is a former State Duma deputy, academic and Russian Ambassador to Tajikistan. Abdulatopiv served as nationalities minister in the mid-1990s under the late Russian president, Boris Yeltsin.

Said Amirov, 59, an ethnic Dargin, has been mayor of Makhachkala since 1998. He has survived several assassination attempts, including one in 1993 that left him confined to a wheelchair.

Magomedali Magomedov, 82, an ethnic Dargin, was longtime leader of Dagestan from 1987 to 2006, when he resigned for unclear reasons. His son, Magomedsalam Magomedov, served with mixed results as head of the republic from 2010 to January 2013.

Magomedsalam Magomedov, 49, an economist and ethnic Dargin, was appointed head of Dagestan in February 2010 by President Dmitry Medvedev. He was replaced in January 2013 after the assassination of the republic’s top judge, and was offered a post of Kremlin deputy chief of staff in Moscow.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox