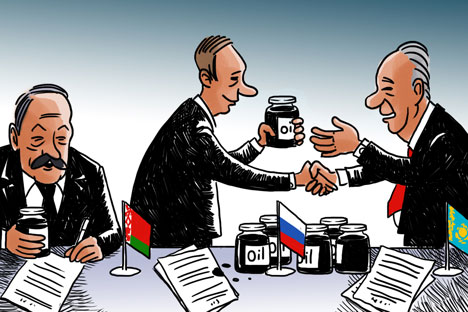

Drawing by Konstantin Maler. Click to enlarge

By signing the agreement on forming the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) with Belarus and Kazakhstan, Russia has taken another step towards deeper economic integration in the post-Soviet space. The new agreement removes barriers to the movement of goods, services, capital and labor, and envisages a coordinated policy in these areas. Earlier, in mid-2011, the three states set up the Customs Union and a year later, a single economic space.

As part of the Customs Union, a single system of foreign trade and customs regulations was created. Powers to pursue a single foreign trade policy were transferred to a supranational body, the Eurasian Economic Commission (EAEC).

In the first two years since the Customs Union was established, its member states recorded a considerable growth in mutual trade. However, last year this growth came to an end. Why was the positive effect of free trade exhausted so quickly?

Rasmussen that cooperation with Moscow on Afghanistan will continue.

The answer lies in the different dynamics of the member states' economic development. In 2011, Belarus was hit by a serious financial crisis, while last year Russia suffered a drastic economic slowdown. Only Kazakhstan demonstrated a stable GDP dynamic in 2011-2013.

According to Deputy Head of the Institute of National Economy Forecasting under the Russian Academy of Sciences Alexander Shirov, the immediate effect of integration has already passed, while the current possible effect lies in evening out the countries' level of economic development.

It is therefore logical that the EAEU agreement envisages a coordinated macroeconomic and foreign exchange policy and sets targets for budget deficit, government debt, and inflation. However, translating these provisions into reality will not be easy.

The most serious obstacle lies in the remaining elements of the administrative command system in the Belarusian economy as opposed to market regulation in Russia and Kazakhstan. Approaches to regulating foreign currency rates also differ.

Belarus has a balance of payments deficit, while Kazakhstan has a small surplus. Given the current structure of the Customs Union member states' economies, only Russia can afford to switch to a completely floating exchange rate. Finding a common denominator is complicated by the fact that the EAEU agreement does not envisage a common monetary policy.

Russia ready to give up restrictions in Customs Union if others do the same - Putin

Over 30 countries want to join Customs Union's free trade regime - official

Russian, Belarusian and Kazakh leaders sign Eurasian Economic Union Treaty

It should be noted that for Russia the foreign trade effect of the Customs Union has turned out to be less significant than for its partners. The current mechanism of the allocation of import duties has turned Russia into the union's donor. The situation began to change only last year when Kazakhstan, for the first time ever, transferred to Russia more customs duties than it had received, while the negative balance in settlements with Belarus dropped to a third of what it used to be.

A generous compensation for these inconveniences came in the form of an export duty on petroleum products manufactured in Belarus from Russian oil. Over a period of four years, it amounted to 433 billion rubles ($12.3 billion).

However, on the eve of signing the EAEU agreement, Russia agreed to reallocate 50 billion rubles ($1.5 billion) of income from export duties on petroleum products to Belarus every year. This means that from 2015, Russia's role as that of a sponsor of integration will increase considerably.

Another serious problem for Russia are the illegal capital flight mechanisms that take advantage of the lack of customs controls inside the Customs Union. In the Russian Central Bank's estimates, the amount of fictitious imports to Belarus and Kazakhstan in 2012-2013 reached $47 billion.

Early this year, Russian banks were instructed to step up controls over foreign trade transactions, while Belarus and Kazakhstan have promised to take similar steps.

Another area where Russia has underperformed is the fact that the ruble has failed to significantly strengthen its position as the main currency for settlements between the union member states. Although the number of ruble payments inside the Customs Union is clearly on the rise, their share in the overall amount of payments in 2010-2012 was subjected to serious fluctuations and did not exceed 56 percent.

Yet on the whole the Customs Union can be considered a success. Whether the new agreement will create further positive effects and the expected synergy effect of an extra $900 billion to the three countries' cumulative GDP by 2030 will be achieved depends on how quickly the member states will manage to remove the existing disagreements and give up national protectionism.

Another cause for optimism is the union's impending expansion. Director of the Russia Academy of Sciences' Institute of the Economy Ruslan Grinberg points out that for a single economic space to function effectively, its population should be 200-250 million people.

The Customs Union and the EAEU documents regulating the labor market were adopted largely bearing in mind the prospective accession to the union of sources of migrant labor such as Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Armenia.

Within the union’s current borders, the effect of liberalization has not been significant because there is practically no illegal migration between the current member states. The expansion of the EAEU and its open labor market will make it possible to legalize up to a million labor migrants and to even out the level of pay.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox