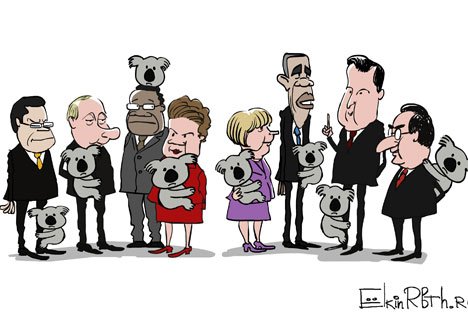

Click to enlarge the cartoon. Drawing by Sergei Yolkin

Vladimir Putin’s ‘tense’ meeting with David Cameron at the G20 summit in Brisbane, where the pair devoted 50 minutes to a "robust" exchange of views over the Ukrainian crisis, finally put paid to any notion that UK-Russia relations will improve in the near future.

The Oxford English dictionary has a term, Godwin’s Law, which covers the use of the ‘Hitler Card’ in debates. Comparing a rival to the Nazis means you have automatically lost the argument. You might expect to find such behaviour in anonymous Internet forums. When a world leader stoops to it, it's hard to see how it encourages further engagement.

Playing the 'Hitler card'

Cameron has twice played the ‘Hitler Card’ this year. In September he used it about Putin during a private meeting with EU leaders. This weekend he repeated it in Brisbane, before meeting the Russian President.

“Russian action in Ukraine is unacceptable. We have to be clear about what we are dealing with. It is a large state bullying a smaller state in Europe,” Cameron said.

Reading his words, deep down I heard the sound of bellicose laughter with a Belfast twang. A British Prime Minister, leader of the Conservative and Unionist Party, accusing a country of bullying small states. How ironic.

In 2010, London was accused of the very same behaviour by little Iceland. “We are being bullied. The British… are using their influence to prevent the IMF programme from going forward,” Icelandic President Olafur Ragnar Grimsson told CNN.

His comments came after the UK used anti-terrorism legislation to freeze Reykjavik’s financial assets. Then, Gordon Brown was British premier in 2010 and Cameron leader of the opposition. However, Cameron didn’t speak in Iceland’s defence. He seems only recently to have seen the light. It's also worth noting that the PM refers to Ukraine as a small state, when in fact the country is about the same size as France, with a population similar to that of Spain.

So, before the pair met, we understood that Cameron's rhetorical tactic would be to compare Putin to Hitler. It seems he also believes that small states should be protected from bullies, unless their name begins with ‘I’. That did not bode well for their meeting.

Poles apart

The last time the two leaders talked, Cameron was trying to coax Putin into supporting a US/UK plan to attack Syria. But British MPs voted his plan down. A couple of months earlier Putin had shown his card on live television when, at a Downing Street press conference, referring to Syrian rebels, he asked Cameron: “Do you want to supply arms to people who eat their enemies' organs?” It was pretty clear that the privileged, Oxford-educated, Englishman and the former KGB agent from St Petersburg have polar-opposite worldviews.

However, they have something in common which divides them. Both preside over post-imperial powers, searching for relevancy in a world where their status is diminished. The British have long played second fiddle to the US. Russia remains an actor in search of a good script. The Kremlin has tried but failed to play nice with the West: think Sochi Winter Olympics or the F1Russian Grand Prix. Putin is now attempting to create an alternative alliance with China and in May signed a 30-year gas supply deal worth $400 billion with Beijing. David Cameron doesn’t like this and obviously doesn’t like Putin. He is also big on talk about Ukraine but short on practical financial assistance, which Kiev urgently needs.

The Russian president had a strange time at the G20, a forum that should play to his agenda. Especially after Russia was excluded from the G8 in March when the Kremlin was snubbed over its annexation of Crimea. Last week in Brisbane, Canada’s Stephen Harper brusquely told Putin to “get out of Ukraine,” and Australia’s Tony Abbot had been threatening to “shirt-front” him, an Aussie rules football term for physical confrontation. As it turned out, before the summit events got underway, the pair was pictured cuddling Koalas, an absurdist vision straight out of Samuel Beckett’s playbook.

Only Ukraine

However, it wasn’t Godot Putin was waiting for, it was Cameron. Their conversation ran late, forcing French president Francois Holland to wait his turn. Cameron, who is no shrinking violet, warned Russia is “risking its relations with the west.” The PM also said that further sanctions against Russia were possible. Additionally, he advocated using drones to monitor the Ukraine/Russia border, a measure that Putin claimed to agree with.

Press digest: Russia isolated at G20 summit as Putin makes early departure

Putin, Cameron focus on Ukraine at talks in Brisbane - Kremlin spokesman

Subject of sanctions was raised at APEC and G20 summits but in general terms - Putin

No soft touch, Putin reiterated that no Russian troops have crossed into Ukraine. Cameron "agreed to disagree" on several issues, including the Kremlin's position that the ouster of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was illegitimate. The pair also addressed Syria, with Cameron suggesting a "national unity government" to replace the Bashar al-Assad regime, which is an ally of Moscow.

Then came the moment that will be remembered when the dust has settled on the Brisbane G20 summit. Putin decided to leave early, explaining it was a long flight home. The world's press thought otherwise, attributing it to the pressure the Kremlin boss had been under.

Cameron declared the weekend's meetings a success for the global economy. A plan to boost global GDP by $2 trillion (or 2%) was agreed. It's difficult to fathom how this will work while Russia, the world's sixth biggest economy by purchasing power parity, is in the doghouse.

Bryan MacDonald is an Irish journalist who focusses on Russia and international geopolitics.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox