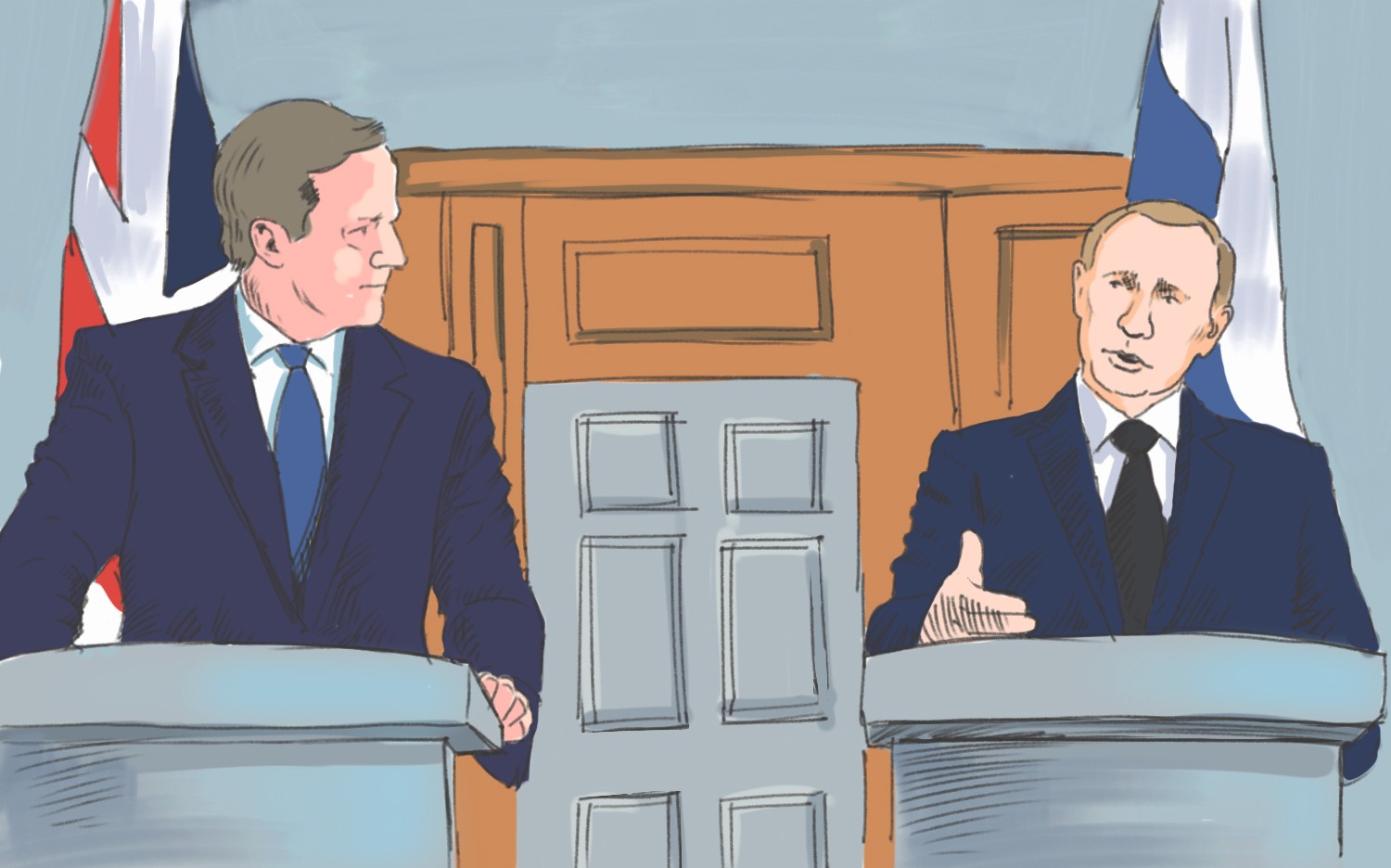

Click to enlarge the image. Drawing by Grigory Avoyan

The new British Conservative Party-led government is the most outwardly anti-Kremlin of Europe’s preeminent players. That does not mean Moscow is not secretly delighted that Mr. Cameron won. While this view may seem paradoxical, it’s rooted in realpolitik. The devil you know is definitely good news for Mr. Putin.

Ed Miliband scared Moscow. While Eton-educated Cameron has in the past last five years developed a true prime ministerial manner, the former Labour leader is erratic - his Russia policy had a tendency to stray into tabloid magazine territory. The low point, from the Kremlin’s perspective, was probably when Mr. Miliband sought George Clooney's counsel on Russian affairs. Much like his Russell Brand stunt it was an attempt to appear cool and “with it.” However, the reaction amongst serious Russia watchers was less polite.

While it briefly seemed that future UK policy on Russia could be influenced by Hollywood, the re-election of Mr. Cameron does mean that it’ll likely continue to be dictated by another great American institution: the White House. The prime minister is a devoted Atlanticist.

Nonetheless, short of a fantasy UKIP landslide, the Westminster election result could hardly have been better for the Kremlin, even though a Labour victory would have taken a British exit from the EU off the table in the short term. It also might have quietened Scottish desires for independence. Conservative rule angers many Scots in the same manner that red rags bother bulls.

Moscow’s dream scenario is a British government it can be friends with. Short of that, Russia would bring Margaret Thatcher back from the dead. In the 1980s all the Iron Lady had to do was bat her eyelids and - like members of her own cabinets - seasoned apparatchiks fell at her feet. Nevertheless, the May 7 result is the next best thing.

All signs suggest that the Kremlin has given up on trying to woo Downing Street for now. Indeed, there have been suggestions that resources are being cut to the London embassy and that minds are now focussed elsewhere. Diplomatic sources privately say they find their UK counterparts “hostile” though honourable.

Mr. Cameron’s return to office guarantees stability and allows the Kremlin to place relations with Britain in a “holding pattern” for now. Had Mr. Miliband been successful, such a policy would have been impossible. Moscow feared that the Labour leader - eager to show he was a “tough guy” - might have allied with U.S. hardliners to increase both rhetoric and sanctions against Russia.

Having dodged that bullet, it’s clear that Russia will operate a wait-and-see position on bilateral dealings with the UK for the foreseeable future. Will Britain remain a single political unit or are the Scots about to finally jump ship? Whither the UK’s place in Europe? Also, what about Boris Johnson? Mr. Cameron has already indicated he’ll stand down before the end of this current term. Will the mayor of London succeed him and steer the ship in an entirely different direction?

Those are all questions for another day. The UK’s relative instability is not a boon for the Kremlin. Russia’s disruptive media often relishes the difficulties of the British elite but that doesn’t mean that diplomats share that agenda. So long as the UK’s relationship with Brussels remains uncertain, it’s difficult to plan ahead. Not to mention that a Scottish breakaway may not actually suit Russia’s long-term geopolitical interests.

The shock election result that gave the Conservative Party victory on 37 percent of the poll when most observers expected another hung parliament surprised many. The question for Russia now is what that victory means in foreign policy terms.

The key element is that Downing Street's foreign policy will not change. Britain remains the most loyal ally of the United States in Western Europe, and will continue to closely coordinate its policy in the Middle East and North Africa with that of the U.S., when it comes to terrorist threats.

However, the results of the general election in the United Kingdom are unlikely to please the Brussels elite. Mr. Cameron is committed to holding a referendum on continued EU membership within two years. “I will not lead any government that does not honour this obligation,” he said during the campaign. “This is a red line. The British people deserve a referendum.”

Surveys suggest that as many as 46 percent of British people would vote to leave the EU, conjuring up the threat of a 'Brexit' from the European club.

The Tory victory means that London's relations with Moscow are likely to remain chilly, even though a Labour victory would have changed little. Shortly before the elections, Mr. Miliband called for tougher anti-Russian sanctions if there were no positive changes in the Kremlin's policy on eastern Ukraine.

Trade is another sore spot. Last year Russian-British trade turnover decreased by 21 percent, compared with 2013. London suspended cooperation on a raft of joint institutions such as the Intergovernmental Steering Committee on Trade and Investment, as well as the High-Level Energy Dialogue.

Meanwhile, some 600 British companies continue to operate in Russia, with the United Kingdom ranked fifth in capital investment in Russia. There are also significant Russian investments in the UK, even if they have declined in recent years for both political and economic reasons.

Russian investment can be summed up in a word: Chelsea. Roman Abramovich's soccer club epitomizes Russian money in London. In truth, there are plenty of prospects for further development of financial and economic relations between Russia and Britain. And economic growth is the mantra that won the Tories the election.

Ruslan Kostyuk is a professor at St. Petersburg State University, Doctor of Historical Sciences. His research interests include European foreign policy.

What does Cameron's victory in UK elections mean for the Kremlin? Read the full opinion by Ruslan Kostyuk at Russia Direct.

Russia Direct is an international analytical media outlet with the focus on foreign policy. Its premium services, such as monthly analytical memos and quarterly white papers, are free but available for subscribers only. For more information about the subscription, please visit russia-direct.org/subscribe.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox