Russia's Navy prepares for practical training in laying of mines in 1912. Source: Open source

It is the year 1854. Russia is locked in conflict with a strong coalition of European countries and comes under pressure across the length and breadth of its territory.In Crimea, Sevastopol comes under heavy siege, while Anglo-French forces attempt to storm Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky in the Far East and bombard the northern port of Arkhangelsk.

The capital St. Petersburg will be next – unless the Tsar’s overstretched fleet can throw up an effective defensive shield around Russia’s "Window to Europe".

As the threat grows from a powerful British naval squadron, a German-born physicist working with the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moritz Hermann von Jacobi, receives orders from the top to prepare a new secret weapon.

While early forms of naval mines had been used by the Chinese since ancient times, this weapon only became known in Europe in the 16th-17th centuries. But the main drawback with early prototypes was their indiscriminate destruction of any vessel once set, friendly forces included.

|

| Moritz Hermann von Jacobi. Source: Wikipedia.org |

Russian engineers hit on the solution in the early 19th century when they fitted mines with electric detonators, using two simple contacts hooked up to a power source on land. The contacts connected as a ship passed and the flowing volts would trigger the explosive charge.

Jacobi also equipped his mines with iron detonator cylinders housed in a wooden cask 28 inches cm tall and 20 inches wide, containing 22-33 lbs of gunpowder. However, the first use of such mines showed that the rudimentary design caused the gunpowder to grow damp.

The engineer subsequently modified the mine housing, adding an additional protective layer of copper and increasing the explosive charge to 55 lbs of powder.

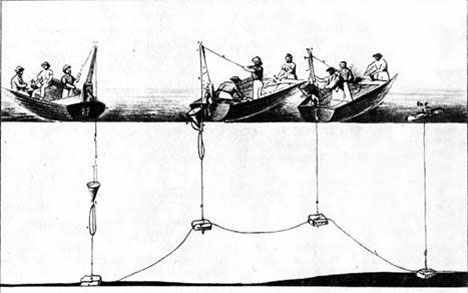

Mine-laying in the Baltic Sea by St. Petersburg began in April 1854 with the placement of 100 units between two artillery emplacements that protected the city, separated by a mile of open water.

The number of charges in this first ever combined mine and artillery screen was increased in June 1855. In little more than a year the entire eastern part of the Gulf of Finland was set with almost 2,000 mines, 500 of which were built to Jacobi’s design and another 1,500 under a similar project by Immanuel Nobel, son of the Swedish engineer Alfred Nobel.

Setting the Nobel mines under the city of Kronstadt. Drawn by E. Nobel. Source: Open source

Four British ships hit mines, but due to the small explosive charge, none were seriously damaged. The mines still did their job, however, keeping the enemy at a good distance from St Petersburg.

The commander of the British squadron reported to London the difficulties posed by "infernal devices" on the port's approaches.

During the Crimean War mines also protected Russian ports in Finland, the mouth of the River Dvina near Arkhangelsk, and the Dnieper Bay in the Black Sea and the Danube delta - a total of 3,000 devices that helped to redress the balance of power between the opposing fleets.

Drawn by Natalia Mikhaylenko. Click to view the infographics.

Mine design was continually improved until the end of the 19th century, demonstrated by increasing explosive power and buoyancy, as well as the navy's technical ability to place them at the desired depth.

In the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78, the Black Sea Fleet’s mining activity virtually paralyzed the activity of Turkish warships.

Mines were also used to great effect in the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese war, employing the new technique of dropping them from conveyor belts mounted on small boats. Each charge held 120 lbs of explosives, which was enough to send the largest ships of the time to the seabed.

The Russian forces laid more than 4,000 mines during the war, destroying 13 Japanese ships, including two battleships.

Like the British and French in the Crimean War, the Germans enjoyed overwhelming superiority at sea in the First World War. The only way to protect St. Petersburg was through the unprecedented mass mining of the Baltic Sea, where 35,000 mines were laid over three years.

The naval command devised some ingenious ruses to protect the mining fleet. In November 1914, mine layers disguised as conventional light cruisers blocked the sea lanes off the coast of Sweden with mines.

Involving the construction of a decoy third smokestack on the vessels to replicate a cruiser’s silhouette, the deception deterred enemy forces from pursuing what they took for much faster vessels.

The Germans’ underestimation of the Russian mining work cost them dearly: In November 1916, the German squadron of 11 destroyers lost seven vessels to mine strikes.

But Britain, the pace-setter in most naval matters, better appreciated Russian skills in mine warfare, and requested that Russia send experts and technology to Britain.

Meanwhile, the Russian fleet coped brilliantly with the task of protecting St. Petersburg, preventing a single enemy ship from reaching the city throughout the war.

Alexander Vershinin is an historian and holds a Ph.D in History. He is a senior researcher at the Governance and Problem Analysis Center in Moscow.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox