Russian Illustrator Valery Barykin successfully combines the vintage Pin Up Girls with Soviet art propaganda.

Valery BarykinThere was always an aura of taboo around sex in the Soviet Union. At the same time, there was, of course, sex. And a lot of it — no less than there is now. It's just that talking about it was considered embarrassing and indecent

Even earlier, back in 1977, Georgi Vasilchenko's book, “Common Sexual Pathologies,” was published, in which he summarized his experiences and described couples he saw in his practice. From his experience, it was clear that many sexual disorders occurred because people did not know how to talk about it.

Words for sex and sexual organs were either obscene or medical terms—neither of which encourage frank discussions.

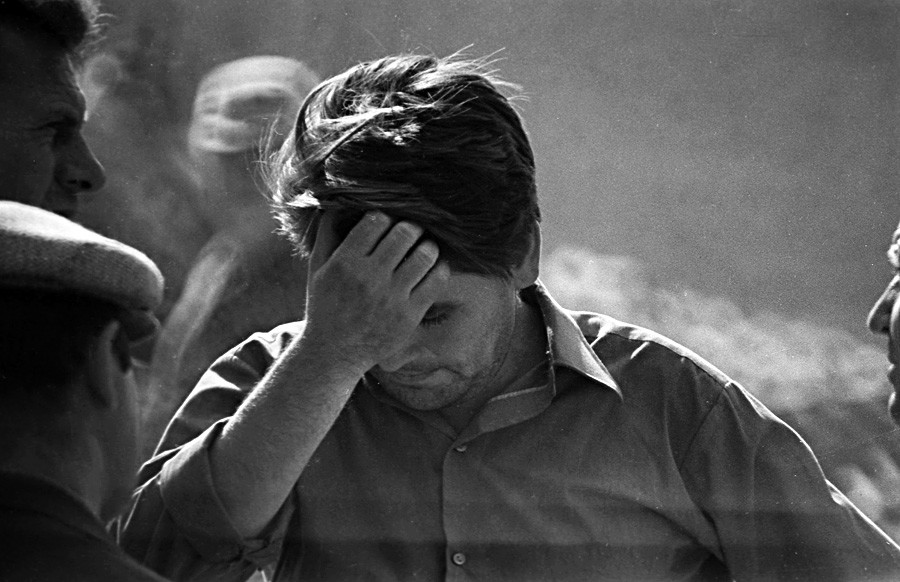

Yuly Raizman's movie "The Strange Woman"

SputnikThere was another scandal in 1978, with the release of the film “Strannaya Zhenshchina” (“The Strange Woman”) about a young man and mature women who fall in love. A review

I was working then at the Diplomatic Academy and learned the news the next morning in a Greek newspaper. It had been picked up by newspapers around the world. Even compared to the West, this was a huge number of divorces.

In the 1920s, the Soviet authorities released the reins on sexual mores. Sexual freedom and emancipation of women were seen as part of the struggle against religion, grammar schools, the teaching of Greek and Latin, work uniforms, and the czarist-era Table of Ranks.

It was at this time that homosexuality was also de-criminalized. Divorces could be obtained without any problem: It was possible to get a divorce without even informing your spouse.

Gymnastics on the roof of a dorm in Lefortovo. This photo by Alexander Rodchenko was taken in 1932, but it perfectly captures the 1920s aesthetics.

Alexander Rodchenko/Multimedia Art Museum of MoscowLater, under Stalin, a more imperial policy was introduced: Abortions were banned, homosexuality was prohibited, and divorces became much more complicated. Even in the 1960s, people seeking a divorce had to put an ad in the Vechernaya Moskva newspaper. Only very powerful people could afford to divorce quietly.

After the war, there was an acute lack of men, so alimony payments were done away with. The issue of recognizing paternity was not even raised. An unmarried woman just left that line blank in the child's birth certificate.

Then,

The police took alimony dodgers to court and sent court orders to them at work. For one child, they had to pay 25 percent of their salary; for two children it was 33 percent and for three or more it was 50 percent.

So men deliberately found low-paying jobs, paid alimony out of that salary, and earned money for themselves on the side. Every alimony dodger was positive that his money was going to feed a slacker—the new husband of his former wife.

Pornographic pictures were very popular. They were sold in trains by people who were, for some reason, called "Belarusians." Actually, they really did look something like Belarusians — blond, with high cheekbones and deep-set, bright blue eyes. They pretended to be deaf, but in reality were not. A dealer would come up to you, nudge your elbow, and take out pornographic pictures.

The pictures could be divided into two unequal groups: The smaller group included reprints of foreign photos, and the larger

Each picture showed an individual scene, and a set of pictures cost 3 rubles. By comparison, a pack of Capital cigarettes cost 40 cents, a bottle of vodka was 3 rubles, and a theatre ticket was 1,5 rubles.

Sometimes the photos were sold as a pack of cards; on the other side of each picture was, for example, the queen of clubs. In addition, there were handmade, locally-produced, pornographic stories with traditional Russian themes.

Later, translations from English appeared, like the famous “Holidays in California” book. A self-published Kama Sutra that had been typed out on a typewriter also made the rounds.

Still, only respectable books like Kafka, Pasternak

In the early 1970s, there was another breakthrough: Little albums with a series of pornographic scenes, like pornographic comics, began to appear in the Soviet Union. They were copied at night. Films also appeared in the amateur 8mm format.

The movies were foreign and professionally produced, judging by the quality. These films were imported mainly from Germany. The movies were like silent movies: One didn't need sound to understand the plot. But there definitely was a plot. All of the movies from the 1960s, 1970s and even 1980s had a witty or funny

Condoms were commonly available in pharmacies. Yet discussing condoms and lubricants aloud was not socially acceptable. Most men came into a pharmacy and whispered faintly, or said, "A bag, please!" or even "Aspirin!" with a wink.

At the time, it was impossible to imagine that a huge glass cabinet with condoms could ever stand in the middle of a pharmacy, or that customers would consult with pharmacists about the quality, taste, color

"Aspirin" cost two cents and came in three sizes. Condoms came sprinkled with talcum powder, so they had to be lubricated either with petroleum jelly or saliva—whatever people preferred. Imported condoms appeared on the market in about the mid-1970s. At first, only Indian ones were offered, and then others appeared on the market

There were other forms of contraception, like today, only they were much less safe. Sexually experienced women would teach friends exactly where to insert a lemon slice. They inserted the lemon right along with the peel.

It worked for the most part. Lemon is, after all, an acid. Women also douched with potassium permanganate. They would jump out of bed and run to the bathroom where they had left a little cup of pink water.

Sex was one of the ways to resist totalitarianism. No wonder Orwell wrote that the goal of a totalitarian state is to subject the body and squash all sexual pleasure. Now there are new sexual dictates—body waxing, chemical peeling

In the past, women were all so different: There were chubby ones, skinny ones, or even bow-legged ones. No one obsessed about it. There was no cult of the

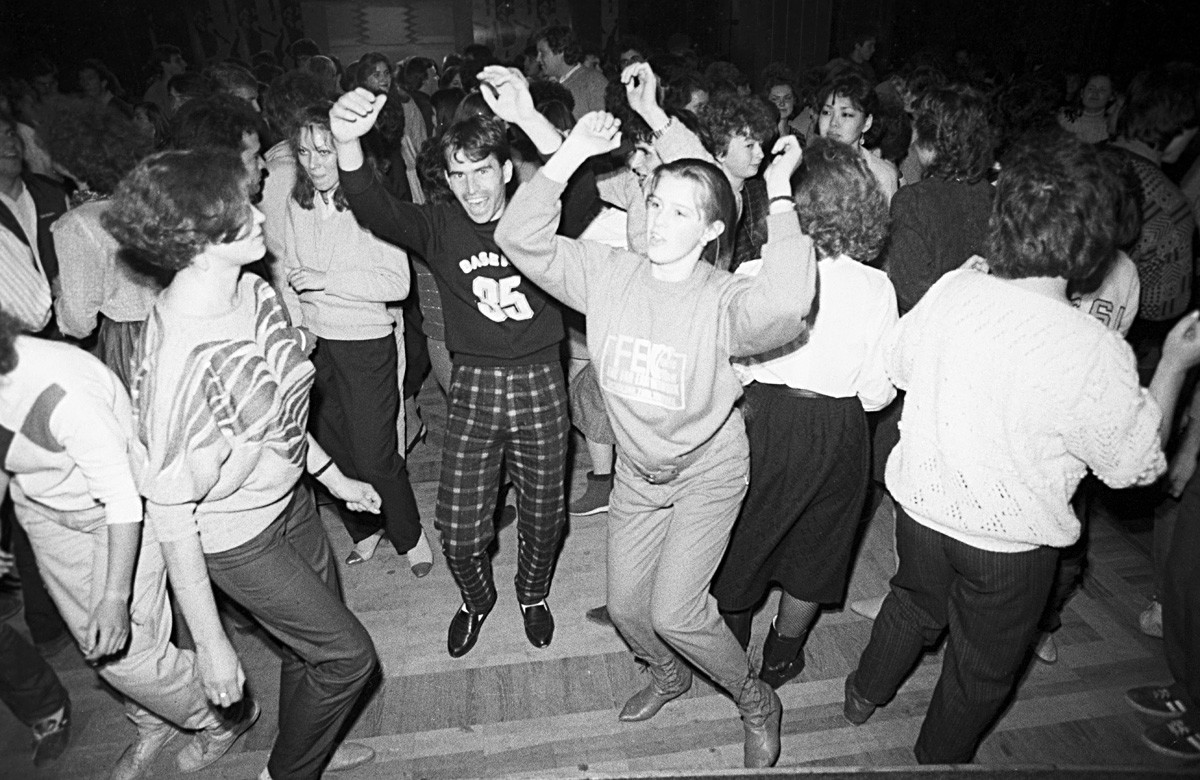

Young people dance at a disco night at the Gorky Park Moscow

Sergey Subbotin/SputnikIn modern Russia, we now have the cult of the plastic, Photoshopped body. It's just another kind of totalitarianism—the totalitarianism of advertising and fashion. In the Soviet

This is why there was less prostitution. It was an era when everything was free, which could not help but spill over into sex. Why pay a prostitute when you could just go out and dance?

Prostitutes waited on the platforms of large suburban train stations. They sat with their legs stretched out and their prices written on the soles of their

The girls usually could be found near the Prospect Mira subway station. They wore rings made of three-ruble or five-ruble bills. One was green, the other was blue, and it was easy to tell the price the girls were asking. But few people went to prostitutes.

Soviet drama "Intergirl"

Pyotr Todorovsky/Mosfilm, 1989Using the services of a prostitute was like paying for drinking water when it was available for free at any water fountain. There were plenty of girls who were willing to indulge in the joys of sex for free.

There was, of course, the risk of STDs. People were afraid of gonorrhea and syphilis, which were very common. There were even street legends associated with them. For example, people knew that the nose could fall off from syphilis, but few people knew that this only happened after about 10 years, if the disease is left untreated. Thus, the morning after a wild night, some guys would, in all seriousness, check their noses.

Problems also arose because the general level of personal hygiene was poor. People bathed rarely and not very carefully. It was said that sexually active girls bathed more often, but proper girls only changed their underwear when they bathed, which was once every four days.

Even in the 1970s, neighbors thought that a female student who rented a room in a communal apartment and took a shower every day must be a prostitute. Back then, it was believed that only a prostitute would bathe every day.

First published in Russian in Bg.ru.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox